In his new book, Weatherhead alum Asad L. Asad demonstrates that rather than hiding in the shadows, undocumented immigrants in the US are selectively engaging with authorities to build their credentials as deserving members of society.

by Michelle Nicholasen

When he began research as a Weatherhead Center Graduate Student Associate in 2013, sociologist Asad L. Asad was deeply interested in the everyday experiences of undocumented immigrants in the US and how the absence of legal status impacted their lives. As he conducted interviews with Latino immigrant families, he noticed how the avoidance of immigration authorities was only one aspect of their day-to-day lives—and conversely, they were also actively engaging with authorities in local institutions: schools, hospitals, the IRS, employment agencies, and the police, among others. He integrated his findings with quantitative data on immigration and deportation for his recent book Engage and Evade: How Latino Families Manage Surveillance in Everyday Life. We asked Asad, now an assistant professor of sociology at Stanford University, to give us an inside look at the realities of being undocumented in the US.

Q: When we hear the word “surveillance,” which is in the subtitle of your book, it conjures up images of drones and cameras. But that’s not at all what you mean in the context of undocumented immigrants, is it?

A: No, it’s much more quotidian than that. It’s about all these mundane institutions that might characterize any person's daily life, but that have added value for people who are undocumented, who need to spend some time managing their relationship with these different institutions.

Q: The irony you point out is that “undocumented immigrants” are actually quite documented, because they actively engage with mainstream institutions to build a positive paper trail for themselves. Based on the hundreds of hours of interviews you have conducted, how do they do it?

A: I should begin by noting that whether you want to cultivate records or not, those records will be cultivated because they are a fact of life for everyone in this country—regardless of legal status. It is just that people who have reason to worry about state punishment, like undocumented people, have to be mindful about how much they interact with these institutions and why they do so.

Take the police, for example. This is an institution that is outwardly threatening to someone who is not authorized to live here because the police frequently collaborate with immigration officers to arrest and deport undocumented immigrants from the country. And yet, despite fears of the police, a lot of my study participants interacted with the police a lot, whether via getting and paying parking tickets and speeding tickets or being pulled over for a broken taillight and the like. So, it’s not that they saw interaction in and of itself as “bad.” Rather, they wanted to minimize their negative interactions with the police and maximize their positive ones.

Q: The assumption here is that positive interactions with authorities will help one’s case when they apply for legal residence. Is this true, based on what you know about the data or from your qualitative research?

A: It is both true and not true. It is true in the sense that if a legalization opportunity one day emerges for people in the study, they will need evidence that they have lived in the country superlatively. But that is a big “if”: many of the undocumented immigrants in my study have lived in the United States for ten years or more and did not see any such opportunity on the horizon.

Q: Let’s step back for a moment and review the eligibility criteria needed to apply for citizenship in the US. Where does one even begin?

A: There are three broad categories of eligibility. The two most common are related to sponsorship—from an employer, or from an immediate relative who is a US citizen or permanent resident and at least twenty-one years old. The third category is humanitarian, as in someone seeking asylum from persecution or danger. Each category of eligibility has its own requirements, many of which are daunting in and of themselves but especially so for people who are already living in the United States without authorization.

Q: So if you are in one of these categories you can apply for a green card, which confers legal residence—and then 3–5 years after that you can apply for naturalization or citizenship, correct? It can’t be as easy as it sounds.

A: It sounds very simple when you put it that way. The experience is anything but. You have to be able to wait several years for your application to even be reviewed. If you're from Mexico, for example, the federal government is currently processing applications submitted back in the late 1990s or early 2000s. It’s not a line that anyone can jump, but it's a line that can have real consequences for people’s lives. Your parents are aging. You're losing your prime work years. And your own health may also be fading. So timing is everything. Many of the people in my book would seemingly become eligible to legalize once their eldest US-born child reached twenty-one years of age, at which point the adult child could sponsor their parent for a family visa, but even that assumes that you can make it nearly two decades in the country without Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deporting you.

So my key point here is that there's a lot that’s in your control, but there is so much that is outside your control, and it just depends on circumstance and context. And as we’ve seen, the laws can change at any time. It seemed like every Friday the Trump Administration would announce some new regulation that would send everything into disarray. Lawyers and advocates had a hard time understanding what the new policies meant and what rights and responsibilities their clients had. You can imagine how hard a time it was for those subject to these new policies and who didn’t have access to a lawyer.

Q: So, it sounds like, to be successful, you have to have good luck, but you also need resources?

A: Absolutely. It’s not random who holds an undocumented legal status in the US. I'm a sociologist. Lacking lawful status is what you'd call a “correlated characteristic.” It overlaps a lot with what it means to be poor, to be a racialized minority, to come from a place where you have minimal access to income and social networks and so on. Immigrants enter the US with all these factors, and once they have settled in the United States, they compound.

Q: Through your fascinating in-depth interviews, your respondents detail the practical hardships they face. Can you give examples?

A: Being undocumented here means that you can't have a social security number where you can work above board. It means that your employers are likely to exploit you and not pay you your due. It means that you can be arrested simply for driving, because you lack a license that your state won't give you. It means that you can't go to the doctor unless you're basically near death, because you can't afford to pay the medical bills, let alone health insurance. It means that you don't have access to public assistance, like public health insurance or food stamps, because the federal government and many state governments exclude you from these resources because you’re an undocumented immigrant. These are just a few examples.

Q: Let me give you a scenario. If a family of undocumented immigrants from Mexico with children who were born there lives in the US for a decade, and all are law-abiding members of society, is there still no pathway to citizenship for any of them?

A: As of today, no. Not unless there was something about their family’s case that made them eligible to legalize under the current immigration system, or unless the current immigration system changes. Those kids wouldn’t even be eligible for DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, for undocumented immigrants who arrived as children before June 15, 2007, among other requirements). And so that's why it really requires some kind of intervention at the federal level. There’s a large group of people who have no real pathway to citizenship. They're trying to lead a good life. They're trying to make ends meet and take care of one another. But there's no real endpoint to their situation without larger intervention, such as marriage (to a US legal resident), or a change in policy and law.

Q: What if another family has some children born in Mexico and some born in the US? Are they eligible for more support?

A: There are some rights that everyone has, regardless of legal status. And one of those concerns the right to K–12 education: every child in the country has a right to public education through high school. After that, college attendance is possible for undocumented students, though there is a lot of variability across states and universities in how much access these students have. One of my study participants has a daughter, also undocumented, who just graduated from UT-Austin and who wants to go to medical school. Texas, though, doesn’t allow undocumented students to enroll in medical school, so the daughter will have to look out of state.

In the context of healthcare, only a child born in the US has a right to public health insurance, assuming they meet income and other eligibility criteria. But this benefit does not extend to undocumented parents, unless they are pregnant with a child who will be born in the United States and live in a state (like Texas) that allows them to access public health insurance on behalf of their unborn child. Pregnant parents who are undocumented are eligible for prenatal care visits and up to two postnatal care visits, but that’s it. Pregnant parents also have access to additional resources, like WIC (Women, Infants, and Children Nutrition Program), but these are temporary.

Q: You describe the many levels of hardship that undocumented people face. And the top level is fear of getting deported, which is something they live with every day. What are the odds of an undocumented immigrant from Mexico or Central America getting deported?

A: There are about eleven million undocumented immigrants in the US today. Although those of all backgrounds are deportable, enforcement is unequal. Mexicans and Central Americans make up 65 percent of all undocumented immigrants and more than 90 percent of all deportations. There is no other group whose lives are more threatened by deportation. The odds of deportation vary greatly depending on what state you live in, what policing in that state looks like, how much police there collaborate with immigration authorities, and so on. But overall, most undocumented immigrants will never experience deportation. Instead, it is the possibility of deportation that frames their daily lives.

Q: We know that our authorities don’t have the resources to actively track down every undocumented person living in the US. So even if you obey the law and live peacefully in the US for decades, are you still at risk?

A: I don't want to overstate the fact that long-term residency in the US without authorization is possible. The average undocumented immigrant has lived in the US for well over ten years, which is a jarring number, right? If they had been granted a green card (legal residency), they would have been eligible for citizenship long ago. So, yes, it is possible to live here long term as an undocumented immigrant.

But I don't want to give the impression that you’ll be OK as long as you obey the law. Because what it means to obey the law is a very subjective classification. You may be able to pinpoint a family and say, yeah, they seem like they're living a good life, and they respect the law, and so on and so forth. But they’re doing all that despite the threat of deportation. Many behaviors are criminalized in this country, like jaywalking, jumping a subway turnstile, and the like. The criminalization and prosecution of these and other behaviors disproportionately target low-income and racialized minorities. And, depending on where you live, these are things that can represent deportable offenses.

Q: What about the raids on workplaces that we hear about in the media? Are they continuing, and what impact does that have on undocumented families?

A: There are what's called “silent raids” that have been increasing since around 2010. These silent raids don't involve deportation per se, but they do involve the Department of Homeland Security, auditing employment rosters at different businesses and threatening employers with fines if they don't fix their lists. So a lot of people get fired or let go that way. Job instability becomes a real impediment to making ends meet for undocumented immigrants and their families, even if they're not necessarily deported following a highly publicized raid. The actual raids, where officers show up to a business and arrest and deport people, are maybe a smaller fraction of the overall deportation regime these days, but they do happen. Raids, silent or not, occur very frequently and make life a lot harder for undocumented immigrants and their families.

Q: In your book, you suggest policy changes that could not only improve the system but also bring more stability to the lives of those who are undocumented. Can you share some of those ideas?

A: In my book, I tried to think very carefully about a range of policy reforms, and I put them into two buckets. In one bucket are the things that we can do to improve what I call “immigration surveillance.” One way to do this is to create a large-scale amnesty program for the undocumented immigrants who are already here and allow them a pathway to citizenship. In my ideal scenario, these immigrants would be allowed to skip the probationary period where they have to live here for a few years as a permanent resident before naturalizing. I would just call being undocumented for ten years “time served” and grant them an immediate pathway to citizenship. I propose other changes, too, like changing the cap on the number of visas that can be issued to any one country, extending or eliminating visa expiration dates, and granting undocumented immigrants in immigration court the right to a public defender.

Another bucket concerns what I call “everyday surveillance,” and it would involve decoupling your citizenship and legal status from your access to societal institutions. But, absent that, I write about restoring undocumented immigrants’ access to a social security number (which they had until 1972!), granting them access to driver’s licenses, and many other reforms spanning the criminal-legal systems, healthcare, education, and public assistance.

Q: Some undocumented workers actually pay taxes in the US, even without a social security number. How does this work, and what advantage does it give the individual?

A: Undocumented people are incentivized to pay taxes on their wages as evidence that they have been living in the US. Some file their taxes using false identity documents, and the IRS actually allows for this; it allows for a mismatch between a person’s name and the ID number on their false identity documents. The IRS knows that those numbers that accompany your name actually belong to someone else, but they are willing to accept your tax payment.

A: Undocumented people are incentivized to pay taxes on their wages as evidence that they have been living in the US. Some file their taxes using false identity documents, and the IRS actually allows for this; it allows for a mismatch between a person’s name and the ID number on their false identity documents. The IRS knows that those numbers that accompany your name actually belong to someone else, but they are willing to accept your tax payment.

The reason why social security remains solvent is because of the contributions of undocumented immigrants who are not allowed to access social security benefits unless they legalize. And even then, if they legalize, they will likely miss out on the contributions they have already made to social security. The same goes for those who work using an Individual Tax Identification Number (ITIN) from the IRS, which many independent contractors do and is perfectly legal and above board. Undocumented immigrants with an ITIN pay payroll and other taxes but they are not eligible to receive social security benefits.

Q: Some states are doing more than others to help undocumented people live their lives more equitably. What are some of the services that are available on the federal and state level?

A: There are some federally mandated services, but there are many more that vary depending on the state you’re in. Every undocumented immigrant has a right to public education from K–12, for example. They have a right to emergency care, but that depends on a physician being willing to provide emergency care and what the hospital deems an emergency. Some states have community health clinics that have special programs for low-income patients, which some undocumented immigrants are able to use. US-born children have the right to public health insurance, but their undocumented parents do not, beyond some prenatal and limited postnatal care for the pregnant parent. Some states grant undocumented immigrants the right to in-state financial aid or tuition benefits at public colleges, including Texas, which you wouldn’t necessarily expect given the context. In California, undocumented immigrants today have a lot of access to various institutions. California just expanded Medicare to undocumented seniors, people over the age of sixty-five, who now have access to Medicare from the state, which is wonderful. Advocates are working to get that expanded to all people who qualify as low income in that state over the next couple of years. So, to live in California is one thing, to live in Texas is a completely different experience.

Contributor Bio

Asad L. Asad is an assistant professor of sociology at Stanford University, where he is a faculty affiliate of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. He was a Graduate Student Associate at the Weatherhead Center from 2013 to 2016 and received his PhD from the Department of Sociology at Harvard University. His new book Engage and Evade: How Latino Immigrant Families Manage Surveillance in Everyday Life is available at Princeton University Press (2023).

Captions

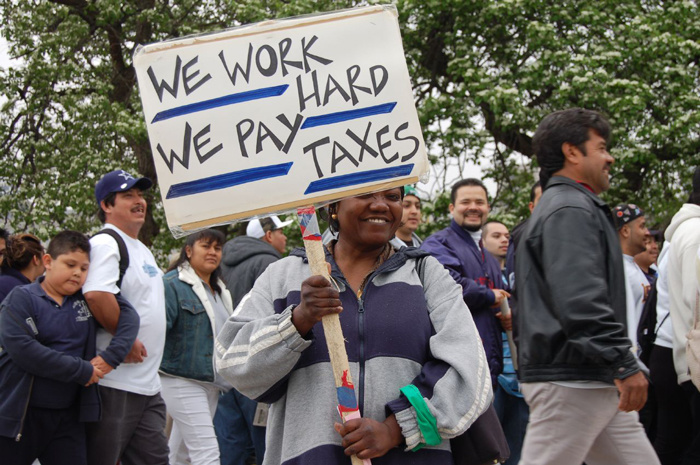

- Chicago Immigration Reform Protest. "We Work Hard - We Pay Taxes." So read the sign of this woman who gladly posed for my camera. She and nearly three hundred thousand others marched on May 1, 2006, in protest for immigration reform. Many were there to oppose the new bill that is currently under debate for legislation: HR 4437. This bill makes all illegal immigrants and those who assist and employ them to be classified as felons. Credit: Araceli Arroyo, Flickr, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED)

- Graph shows top US deportations by country. For estimates of the overall number of undocumented immigrants by country, living in the US, see Migration Policy Institute. Source of data: ICE. Graph credit: Michelle Nicholasen

-

Defend DACA Protest, Los Angeles, 9-5-17. Credit: Molly Adams, Flickr, (CC BY 2.0 DEED)

DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) was originally established via executive action in June 2012 to protect certain undocumented immigrant children from removal proceedings and allow them to receive authorization to work for renewable two-year periods. To be eligible, individuals must have arrived in the US prior to turning 16 and before June 15, 2007; be under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012 (i.e., under age 41 as of 2022); be currently enrolled in school, have completed high school or its equivalent or be a veteran; and have no lawful status as of June 15, 2012. The program has enabled over 900,000 immigrants to stay in the US, go to school, and contribute to the economy through employment. In 2023 both a federal and district court in Texas ruled DACA illegal, blocking first time applicants. - Infographic called “Undocumented Immigrants Pay Taxes Too” describes taxes paid by undocumented immigrants. Credit: Institute on Taxation, Flickr, (CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED)