A historian working in Vietnam reflects on the past events that shaped the country’s response to COVID-19.

By Michelle Nicholasen

By all accounts, Vietnam has been extraordinarily successful in containing the SARS-Cov-2 outbreak. With just 335 cases and, remarkably, no deaths reported as of June, Vietnam may offer some tactical lessons for controlling the next pandemic—regardless of which countries would be capable of adopting them.

Vietnam was the first country to tighten its border with China in late January, and acted quickly to contain its first fifteen cases by immediately isolating and quarantining sick and exposed individuals. By late February, it had cleared the first wave. On March 22, it suspended entry of foreigners, with some exceptions, and required returning citizens to quarantine for two weeks in a state-sponsored facility. A second wave occurred with about sixty cases, when an individual returned home from Europe. That too was contained in about a month’s time, and local transmissions continued at a low rate. By late June, Vietnam recorded fifty-eight days of no new cases via community transmissions.

To get a deeper picture of the Vietnamese experience during the pandemic, we turn to former Graduate Student Associate Andrew Bellisari, who is a founding faculty member of Fulbright University Vietnam, the country’s first independent nonprofit liberal arts university, to ask him about life in a communist country during a pandemic. He teased apart the various interpretations, both historical and political, that may—or may not—explain Vietnam’s success in controlling the spread of the virus.

Q: What did Vietnam get right?

A: The Vietnamese government has been lauded for its decisive actions; restricting travel to and from China was one of the first things it did when the first case was confirmed, around January 23, following the return of a sixty-six-year-old Vietnamese citizen from Wuhan.

It immediately began tracking confirmed cases. Contact tracing has been an extremely effective measure of the Vietnamese government—I would say even more so than testing. One of the most dramatic quarantine measures early on was at a locality a few dozen kilometers outside of Hanoi in Sơn Lôi commune. About ten thousand people were completely quarantined because of six cases.

Q: What did you notice happening in your immediate surroundings?

A: My apartment building put up plastic sheeting over the elevator buttons. They closed the pool, then drained the pool. They also used bicycle or motorcycle locks to lock all the doors except the main entrance, creating what would be a terrible fire hazard anywhere else in the world. But the whole idea was to funnel the residents through the lobby where someone could check your temperature.

Q: When you arrived in the United States, I’d guess nobody took your temperature. Did that seem strange to you?

A: A little bit. I was certainly amazed when I arrived in the United States on the twenty-fourth of March and no one at Dallas/Fort Worth, which was my point of entry, took my temperature. I think they asked me where I had been and that was it.

Q: Then you were free to exit the airport, no doubt. That contrasts with the forced quarantine of all travelers arriving in Vietnam, who are/were put up in hotels or government facilities and taken care of for two weeks.

A: The Vietnamese government has made all quarantine and all treatment free for Vietnamese citizens. All quarantine accommodations are free for non-Vietnamese as well, however they have to pay for any treatment.

If you had the money, you could actually quarantine in a pretty nice place in Vietnam if you were a foreigner who arrived before the ban. It wasn't all army barracks and that sort of thing. But for most people, you're going to find yourself in facilities that have been converted precisely for this purpose. It was a very conventional response, in that the discomfort and the inconvenience was upfront very early. I think as of April, Vietnam had quarantined up to 50,000 people inside the country.

Q: Many might look at Vietnam and say, well, it’s a communist, centralized government so of course they can control their citizens’ behavior because everybody follows orders.

A: The decision-making power is maybe not as monolithic as we may think in a country like Vietnam. In the very beginning of the crisis, municipalities were making decisions, too. For example, Ho Chi Minh City made different decisions from Hanoi. There really was a lot of uncertainty as to what the next step would be. The closure of schools, for example, was never initially going to last as long as it did (note: schools have generally reopened in Vietnam as of May).

As a historian, I’m always cautious whenever I read commentaries that use overgeneralizations about Vietnam being a “collectivist” society to insist that there must be a cultural reason for why Vietnamese people follow certain public health measures or can tolerate inconvenient situations. Actually, I don't believe that to be the case. The US is perhaps, by definition, more socialist than Vietnam in terms of providing for education, healthcare, and other social services. For example, healthcare is not generally free in Vietnam. Public education is not free. Vietnamese citizens have to pay a nominal amount, but they still have to pay for both.

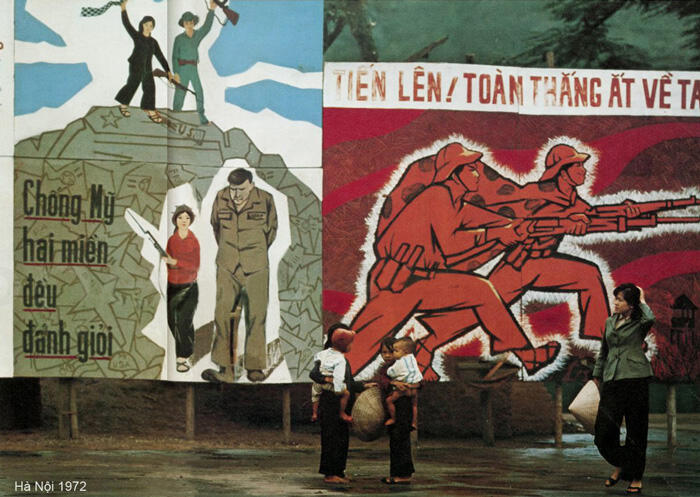

I think history explains much more than any orientalist ideas of Asian “collectivism” in this case. In Vietnam, what outsiders might perceive as collective discipline is a product of a very traumatic history of citizens being called upon to mobilize and survive during and after wartime—whether in the war of decolonization against France, the Second Indochina War, the economic challenges that afflicted the country after 1975, or the armed conflict Vietnam engaged in against Cambodia and China in the late 1970s. I would argue it’s less some essentializing idea of so-called East Asian values that's motivating people to wear masks and “follow the rules” than the historical imperative of what it means to maintain solidarity in the face of adversity. We shouldn’t forget that there’s a living memory of wide-scale mobilization, sacrifice, and trauma in Vietnam that does not exist to the same extent for most people in western Europe or the United States.

Q: How exactly does collective memory come in to play in a pandemic like this?

A: I think in several ways. One of the main sources of the Vietnamese Communist Party's legitimacy today is its success in the war. Being able to tap in to the triumphalist rhetoric of average people mobilizing for victory resonates quite strongly in Vietnam.

The government has very effectively deployed rhetoric similar to what the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the National Liberation Front had used to mobilize people during the war. The prime minister, Nguyễn Xuân Phúc, has said “fighting the virus is like fighting the enemy.” The Vietnamese state has gone full-in on the war analogies.

There’s also a certain sense of national pride and patriotism, even among the younger rising generation that is very proud of the progress Vietnam has made in the last twenty years, despite also being wary of the instruments of power that exist in the country. Vietnam’s current success against COVID-19 is an immense source of pride for everyone in the country.

Q: Vietnam shares a border with China. Did proximity factor into its fast response to the outbreak?

A: The Vietnamese government, maybe more so than any other country, was very prepared for this scenario, because it was the first country after China that had confirmed cases of SARS in 2003, and it also had to handle the swine flu pandemic in 2009. This is a country that knew that successful public health responses were critical to the state's continued authority. It also knew just how small the margin for error was.

Perhaps one more piece of the puzzle that explains why the Vietnamese have been so successful at mobilizing against the coronavirus is the idea that the response to the pandemic was an opportunity to set themselves apart from the Chinese. This is my analysis, no government spokesperson would say as much, but the underlying sentiment amongst the Vietnamese is that COVID-19 is a problem that once again came from China, just like SARS, and the Vietnamese people are going to fight back against something that's seen as coming from China. That may seem very simplistic, but I think it gets at a very particular sense of national identity—one that is very effective.

Q: It sounds like the pandemic has fostered positive feelings toward the government?

A: Anecdotally, that's what I've heard, too, from friends, colleagues, and students, which is that they're trusting the government to tell them the right sorts of information. My students tell me that in the past that wouldn't have been the case. So, there is a bit of a shift here in how people are responding to government communication.

Q: But right before the pandemic, there were notable public protests against the Vietnamese government, which is remarkable to see in a communist country. Can you recount those incidents briefly?

A: Outside observers think of Vietnam and they tend to think of it only as a single party, communist state. And while that’s true in its mechanisms of power and in its rhetoric, it’s not very communist anymore in the economic sense of the term. And the party itself has been facing a series of challenges over the past five years.

As recently as this January, there was a very dramatic episode that happened outside of Hanoi in a town called Dồng Tâm, where the villagers protested against the government’s plan to expropriate land. The villagers used hand grenades and petrol bombs. Three police officers were killed. One villager was shot. That is almost unheard of here.

Before that, in 2016 there were protests over the Formosa Ha Tinh Steel Corporation

that had been polluting the waters off central Vietnam and led to the death of the local fish population. Further, in June 2018 there were a series of protests over two pieces of legislation being proposed at the time: one about a cybersecurity law and the other over the creation of special economic zones that citizens feared would allow Chinese developers to control Vietnamese land.

Q: Now add the pandemic, where citizens must turn to the government, in spite of recently growing distrust. How has that changed the dynamic?

A: This is the moment in which the Vietnamese government had to be responsible. If they messed it up, the popular response could have been extremely negative. Ironically, that produced high levels of communication and transparency and maintained the image that the Vietnamese government was acting in the best interests of the people, and the citizens responded extremely well to that.

Q: How badly wrong could things have gone?

A: I'll draw a historical kind of parallel, which is to say, for a state built on a tradition of armed popular revolution, history is dangerous, because officials know the success the people have had and what they are capable of. It is built into the story of the modern Vietnamese state.

The US Congress, the White House, they're not really worried that people in New Jersey are going to rise up because they're annoyed with social distancing measures; it's just not going to happen.

In Vietnam, what's so sensitive about the popular movements of the last five years is they're organic. The state can't claim that it’s foreign meddling or agents provocateurs trying to undermine the Communist Party. Officials have to respond to the people who are organizing.

Q: But in the US, there are protests against states shutting down businesses during the pandemic, even vigilantes with guns protecting shop owners from the police.

A: Maybe the difference in responses is that no one can seriously think that the United States government is going to fall. Or the British government is going to fall. Or the Italian government is going to fall because of the public health care crisis. Protesters with AR15s outside the Michigan State House, that’s just another week in the United States somewhere, right? No one will seriously believe that the government is going to topple.

I don't think anyone in Vietnam would cause an uprising. It's highly unlikely. But that doesn't stop political leadership from having to face the existential anxiety that it could happen. Because it did happen only fifty years ago. That is just something that policy makers in the United States and in western Europe don't even have to think about.

Q: The US has had more than 100,000 deaths and Vietnam has reported none. How does this look to people in Vietnam?

A: One of the truly positive stories of the last decade has been the continued growth of US-Vietnamese reconciliation. It’s been twenty-five years since the US began normalizing relations with Vietnam. Fulbright University Vietnam is very much a part of that story and that history. To be quite frank, many Vietnamese today look upon the United States in a way that would have been unthinkable half a century ago. For the most part, all I've heard are expressions of concern for how bad the pandemic is in the US and support for Americans.

Q: One can hope that the US, which is suffering greatly in its response to the pandemic, can learn strategies from countries like Vietnam in anticipation of the next crisis. Do you think the US will be open to learning lessons from the countries in Asia?

A: I think the United States will need to have a very honest and frank conversation about what happened and what could be done better. But to try to fasten the response to cultural identity or cultural values misses the point. I don't think there's anything in particular about what it means to be “Asian” or “Chinese” or “Vietnamese” or “American” or “Western” that necessarily directed the response. Rather what are the realities of the public policy-making options that are available in these places? What did each prioritize? Vietnam had all of the levers of state power necessary to pull in order to control the situation as quickly as it did. The United States didn't. I think policy-making options did direct the two different responses. I’m not sure that's necessarily a lesson to be learned. But merely an observation to take into account.

—Michelle Nicholasen, Editor and Content Producer, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs

Former Weatherhead Center Graduate Student Associate Andrew Bellisari is a founding faculty member of history at Fulbright University Vietnam. He received his PhD in history of modern Europe and the Middle East from Harvard University in 2018. His research explores the political and cultural processes (and consequences) of decolonization across the French empire, particularly in Algeria, and he has published his work in the Journal of Contemporary History and the Journal of North African Studies.

Captions

- Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc has declared “Chống dịch như chống giặc” (“Fighting against the epidemic is like fighting against the enemy”). Vietnam’s COVID-19 messaging has often recalled wartime Communist propaganda, both in its rhetoric and its visuals. Here civilians gather in front of propaganda posters in downtown Hanoi, circa 1972. The poster on the left reads, “Against America, both regions [i.e. North and South Vietnam] are skilled at fighting,” while the poster on the right proclaims: “Advance! We will win no matter what!” Photo credit: Hanoi 1972, photo by Ishikawa Bunyo, Flickr user manhhai (CCBY2.0)

- A Vietnamese People's Army officer wearing a protective facemask amid concerns of the COVID-19 coronavirus stands next to a sign warning about the restricted area set up in the Son Loi commune in Vinh Phuc province on February 20, 2020. - Villages in Vietnam with 10,000 people close to the nation's capital have been placed under quarantine after cases of the deadly new coronavirus were discovered, authorities said. Photo credit: NHAC NGUYEN/AFP via Getty Images

- Hanoi's Mayor Nguyen Duc Chung (3rd R) is greeted by villagers at Dong Tam commune, My Duc district in Hanoi on April 22, 2017. More than a dozen police and officials held hostage by Vietnamese villagers over a land dispute were released on April 22, state media reported, ending a week-long standoff that had gripped the country. Photo credit: STR/AFP via Getty Images