Over a period of ten years, Annette Idler conducted fieldwork along the volatile borderlands of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador to better understand how life proceeds in a gray zone, where the government has abandoned you, and where the rule of law does not exist.

By Michelle Nicholasen

This is the first of a two-part interview with Weatherhead Center Visiting Scholar Annette Idler about her work on conflict-ridden borderlands. Read part 2 on Epicenter.

Conflict and lawlessness often put down roots in the most remote, unsupervised corners of a country. When she was a doctoral student in international development at the University of Oxford, Annette Idler was drawn to areas of conflict because she believed that is where suffering is greatest, and where she felt research efforts could help the most. Colombia’s borders with Ecuador and Venezuela made for the perfect crucible of insecurity. The geopolitical situation there had long been intense, and over the course of her work, Idler witnessed a cascade of changes, including the rise of violent nonstate actors and drug trafficking that forced people to constantly adapt to the security dynamics imposed by armed groups.

When Idler first entered the scene in 2008, the Ecuadorian border was precarious. Colombian forces had just conducted a military attack on the guerilla group FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), who were hiding just across the border. This incursion into Ecuadoran territory frayed relations between the two countries and heightened fears of interstate war. Since then, bilateral relations have improved again but armed groups are still taking advantage to operate on both sides of the border.

In 2016, a peace agreement finally ended the FARC’s fifty-year guerilla campaign against the Colombian government, but the long process of demobilizing the rebel group created a power vacuum. Up to that time, the FARC had created a dubious kind of security for its citizens in the border areas, by providing some social benefits and protection for its citizens in exchange for obedience, an arrangement Idler refers to as “shadow citizen security.” But after the combatants laid down their weapons, it didn’t take long before various violent, nonstate groups entered the arena and vied for power, often violently, in the regions formerly controlled by the FARC. Although the peace accord was hailed a great success internationally, the aftermath has been severe. More than 300 human rights defenders have been assassinated—some believe systematically—by former paramilitary groups that still operate, cocaine production is on the rise, and there has been an expansion of FARC dissidents acting on their own. The ELN (National Liberation Army), the largest extant guerilla group, is still active and fighting in some regions.

Problems in the region intensified after the collapse of Venezuela’s economy, when refugees began flooding into Colombia in 2015–2016, further straining and sidetracking Colombian institutions. To date, nearly five million people have left Venezuela, 1.8 million of whom fled to Colombia. In fact, the size of the Venezuelan exodus is approaching that of the Syrian civil war. “When I started, it was Colombians fleeing to Venezuela to get away. And towards the end, it was the other way around,” Idler says.

Idler worked inside the two border areas during the volatile years of 2008–2018, conducting 606 interviews with all categories of stakeholders in the region, including excombatants, displaced people, military and police officials, drug traffickers, civil society leaders, as well as NGOs.

In her recent book, Borderland Battles: Violence, Crime and Governance at the Edges of Colombia’s War, she synthesizes her findings into a phenomenon she calls the “border effect,” a confluence of factors that create long-lasting insecurity. Geographically, many of the border areas of Colombia are in hilly, jungle terrain, and are difficult to reach. There is a lack of infrastructure and roads, and there is a lack of basic services such as health and education, cutting off the borderlands from the economic and political center of the country and its institutions. All of this makes for a “low risk/high-opportunity environment” for illegal economies, Idler argues, because there are few state-sponsored institutions. Indeed, it’s often the case that government officials themselves have a stake in the illegal economies, resulting in low incentive for change.

Today, in her role as an academic, Idler directs two research programs she established, one that extends her research methodology to other regions around the world, and one that uses research findings to advise state leaders on transitioning relevant stakeholders in their countries from “conflict actors to peace architects.” We sat down with Idler to ask her about her experiences in the border regions, and how effective interventions can emerge from academic research.

Q: Who are all the groups jockeying for power at Colombia’s border areas?

A: Colombia is a multiparty conflict, the two main rebel groups being the FARC and the ELN, with the latter still active. Then there are the paramilitary groups. In the 1980s, traffickers, important landowners and the government formed self-defense groups against the guerrillas and they evolved into a parliamentary umbrella organization, called the AUC (United Self Defense Forces of Colombia). They were created to fight the guerillas. They demobilized in the early 2000s. But this demobilization process was not very successful because successive groups emerged and now there are many smaller groups—they are basically still right-wing groups. Many government officials argue they are just criminals and they have nothing to do with the paramilitaries. But, in fact, a lot of them are the same people. They now fight the guerilla or leftist groups, but also are very much involved in the drug trade.

So this is an important dimension in the Colombian conflict. It is not just about ideology or political goals. There's lots of economic interests involved. And that's why we see criminal groups that are also trying to control certain routes and important strategic harbor towns. Even the Mexican cartels are present in Colombia. So you have this mélange of the politically motivated groups that are against the government, then politically motivated groups that are more or less supporting the government, and then many in between.

Q: Since the key goal of your fieldwork was to understand life at the periphery, can you paint a picture of what it’s like to be a resident of a border town that’s not under the protection of a sovereign government?

A: Everyday life is shaped by living under this nonstate order. It is important for people there to always know the dynamics of the different groups that rule their area. It’s easier to operate under a system that has only one group in charge, if you accept the order that is imposed. In some areas there were open clashes between the paramilitaries and the guerillas, and even though it’s a situation of war, at least people knew who was on which side. But then there's other areas that are much more complicated, like in Maicao in the north of Colombia or Tumaco on the Pacific coast, where there are so many different groups involved, people really couldn't understand who's on whose side and for how long. You can’t say “I’ll support this one group so that they leave me alone,” no, because another group would come in and say “we are now ruling here, you have to pay us now.”

Q: So, there is really no local police to whom they can turn?

A: That is the dilemma for the local population: you can’t go to the police to be protected, because you are scared that the police are involved in the illegal trades, or there's simply no presence of state institutions.

Q: Did you witness any of the violence first-hand?

A: I was on a motorbike taxi shortly after a grenade was thrown into a shop. And I asked the driver what happened and he said, well, you know, that the guy probably didn't pay the vacuna, or taxes/fees, to the group in control. So it's his fault if his shop is destroyed. Why would you not pay the vacuna? he said. So the people have even internalized that you are the guilty one if you're not sticking to the rules. It's not one single incident, that's happening in many places.

Q: What are some other imposed rules citizens must abide in order to keep life moving?

A: These controlling groups impose curfews in many areas. You are not allowed to be outside after it gets dark. And if you're outside, groups would distribute pamphlets or flyers basically saying what will happen if you don’t comply. There were even cases where they would impose what people should wear in terms of clothes. Then of course there's punishment against thieves, against rapists. So that's a kind of social cleansing that these groups demand, which on the one hand imposes order. But then again, there were cases where they were punishing gay people, for example. So, these are very strict rules and you basically have to follow them, and you can't really change anything.

Q: Do border residents feel deterred from regular movement?

A: On the day to day, I think the hardest part is mobility. It’s safer to stay at home or in the local area because the roads can be dangerous. You don’t know who’s going to impose a checkpoint and ask for money or harass you. There were—and still are—many cases where people are confined to an area, or restricted by landmines set up by the armed groups to prevent the movement of the local population, presumably so that they would not share information with other competing groups or the government.

One horrific thing we see right now, especially in the context of the Venezuelan crisis, is not only are people charged a fee for crossing the border, but women are being sexually abused after they cross.

Q: How does the population cope with the curtailment of their freedoms?

A: What I found very admirable is to see how those communities, despite all the pressures, just get on with their daily lives and help each other out whatever way they can. And in many parts, despite all the suffering, they're very positive. They have a very positive outlook on life. They're very optimistic on the one hand, but then on the other hand, of course, it's also about daily survival. You’re not able to think about what will happen in five years because you have to make sure you maintain your family the next week. It's a very short-term thinking because it's the only way to move forward.

Q: What about Colombia’s borders with its other neighbors: Brazil, Peru, and Panama? Is there a “border effect” there?

A: Yes, the border effect is a phenomenon that occurs in any vulnerable regions where state capacities are weak, neighboring countries do not entirely coordinate their respective law enforcement efforts, and their economic systems differ from each other. This turns border areas into spaces of impunity and illegality. It’s like a filter mechanism whereby criminal and conflict actors can easily cross the border, but state officials cannot. At the Colombia–Panama border for example, this is evident in the significant human trafficking occurring there.

Q: About twenty years ago the US intervened with a military strategy to help Colombia combat both the rebels and the drug trade. Some say its success was born out in the subsequent peace agreement with the FARC, although there were some egregious human rights abuses along the way. Do you think the US has a role to play in the borderlands, where the drug trade is now concentrated?

A: I've briefed the State Department quite often on their strategy toward Latin America over the past four years. And of course, the US has a huge role to play. I think the US should insist on implementing the peace agreement (between Colombian government and the FARC). It includes important elements that will help reduce insecurity and reduce the drug problem—for example, measures related to an agrarian reform or the participation of local communities in deciding what is good for them.

Reinstating toxic sprayings as recently suggested by the US president does not solve the drug problem—quite the contrary, we have considerable evidence that they also have severe health and other negative impacts. And of course, let’s not forget why there is so much supply: because of the vast cocaine demand in the US. Reducing drug-related violence in Colombia’s borderlands also starts with reducing demand at home in the US.

They should also insist on making sure that development reaches Colombia’s border areas. I mean, solutions could be so easy, right? It's building roads, electricity, basic services, health, and education in those areas where you don't have that.

Why is it that so many farmers who work in coca cultivation used to produce cocaine? Maybe they don't have any alternative crops, but if they do have them, there's no road that would allow them to take the product to the market. Cultivating coca is easier: financiers come to their farms and pick up the leaves or the coca paste to process it into cocaine.

I work on Myanmar and Somalia as well. There you have other dimensions of religion, of ethnicity, of groups that want independence. You don't have to deal with all these aspects in Colombia. It could be much easier in a way. It's just about making sure that there is the political will to also deal with that.

—Michelle Nicholasen, Editor and Content Producer, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs

In part two of the interview, Annette Idler discusses how her research organizations operate and the impact they’ve had in other countries with enduring conflicts.

Annette Idler is a Visiting Scholar in the Weatherhead Scholars Program at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. She is also the director of studies at the Changing Character of War Centre, senior research fellow at Pembroke College, and at the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford. She is principal investigator of the Changing Character of Conflict Platform and of the CONPEACE Programme at Oxford. Annette Idler has conducted extensive fieldwork in war-torn and crisis-affected borderlands, including in Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Myanmar, and Kenya (on Somalia) analyzing people-centered security dynamics.

Captions

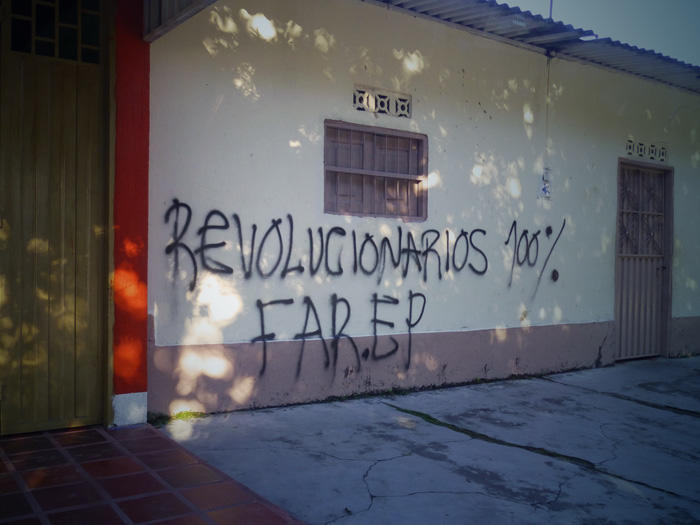

- Graffiti on wall of building in Arauca, Colombia, September 2012, in a village that was controlled by the FARC. Credit: Annette Idler

- Map: Violent Nonstate Group Interactions along the Colombia–Ecuador Border. Adapted from Borderland Battles: Violence, Crime and Governance at the Edges of Colombia’s War, page 86. Credit: Used with permission from Annette Idler

- This is a 2004 flyer the FARC distributed to citizens at the Colombian–Venezuelan border. In it, the FARC denies responsibility for the recent murder of six Venezuelan soldiers and a civilian engineer in a nearby town, and blames right-wing paramilitary actors. The communication is significant because the FARC addresses citizens in both countries as if the border does not exist, as if they are part of the same community. Also significant is the FARC’s professed support for the Venezuelan “revolutionary” army. A few years later, the region would erupt in guerilla-on-guerilla conflict, with the FARC entering armed conflict with the ELN, allegedly supported by the Colombian military on the Colombian side and by the Venezuelan military on the Venezuelan side of the border. Credit: Used with permission from Annette Idler

- The Colombian side of the border between Arauca, Colombia and Apure, Venezuela. Idler had crossed the border at this bridge until 2015/2016 when Venezuelan president Maduro shut the border, which triggered a humanitarian crisis, an event she wrote about in an essay. While this official border bridge was closed, smuggling and drug trafficking continued at the numerous informal border crossings along the porous border. Ironically, the sign on the barricade says “welcome,” even though the border is closed; and, “In this country Chávez lives,” even though Chavez died a few years earlier from cancer. Credit: Used with permission from Annette Idler

- Colombian drug squad policemen stand guard next to an improvised lab at a coca plantation in a rural area of Puerto Asís, department of Putumayo, Colombia, on the Colombia-Ecuador border, on September 27, 2013. Credit: LUIS ROBAYO/AFP via Getty Images