Sarah Dryden-Peterson, associate professor of education at Harvard, shares insights from her team’s work on refugee education around the world.

By Michelle Nicholasen

Of the sixty-five million people currently displaced worldwide, about half of them are children. On average, a refugee may spend between ten to twenty-five years in exile. This means that for many children, their entire formal education will take place while awaiting a durable solution to their displacement. However, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that only 50 percent of refugee children have access to primary education, and only 22 percent have access to secondary school.

The critical task of educating refugee children has been the focus of scholarship for Weatherhead Center Faculty Associate Sarah Dryden-Peterson and her research team who are investigating processes of refugee education in Kenya, Lebanon, and Uganda, among others. Documenting the experiences of students, families, and teachers over time, the group has gained insight on education delivery, quality of instruction, and resource allocation. The struggle to meet the educational needs of refugee children, according to Dryden-Peterson, has called into question the very purpose of education and what kinds of futures it prepares young people for.

The Weatherhead Center asked Dryden-Peterson and doctoral students Vidur Chopra and Elizabeth Adelman to describe some of the realities facing Syrian refugees, who rely on education as a critical pathway to establishing a secure life. What follows is an abridged version of that conversation.

Q: What are some of the guiding principles of your team’s work?

A: Our work seeks to understand the links between education and conflict. So, for example, what are the ways in which education can exacerbate—and mitigate—conflict? But while we look at conflict, our view is always on possibility and opportunity. We want to understand the links between education and conflict so this knowledge might contribute to educational opportunities that foster durable peace.

In our work on refugee education, we also take a long-term, developmental approach, which can run counter to emergency and humanitarian mindsets that tend to focus on the immediate, the here and now. The nature of conflict has changed such that displacement resulting from conflict is about three times as long as it was in the 1990s. This kind of protracted conflict means great uncertainty for refugee children and their families. They don’t know if their futures will involve a return to their home country, a long-term exile in a neighboring country, resettlement, or onward migration—or some combination of these experiences. Given these realities, our research points to the importance of refugee education that prepares children for multiple possible futures.

Q: How do you devise a curriculum that teaches the concept of “multiple possible futures”?

A: In our fourteen-country study of refugee education, national and global education actors—as well as teachers—consistently described education as a set of tools for young refugees to navigate the unknowable futures they face. Some of these tools include basic academic skills, including literacy and numeracy. But they also include “navigational capacities” that allow young refugees to build productive and stable relationships and create opportunities. To do so, these children need strong social skills as well as analytic skills that allow them to both understand and disrupt unequal opportunity structures. Any of this learning depends on young people feeling welcome and included—also critical dimensions of curriculum and pedagogy.

Q: What does the commitment to education look like at the host-country level?

A: The human right to education follows an individual, no matter where they are geographically, and no matter whether or not they are a citizen of the country they inhabit. Yet all countries have resource constraints—and most of the countries that host the largest numbers of refugees struggle to provide a quality education for all children.

We see this in Lebanon, where only about one-third of Lebanese nationals attend public schools. Yet even so, and despite the large numbers of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, the Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education has facilitated Syrians’ access to public schools. The education system has needed to respond to changing conditions. When refugee enrollment increased such that the student body doubled, the system became overloaded and so two shifts were created: Lebanese nationals attend school in the morning and, in the same buildings and often with the same teachers, refugees attend school in the afternoons.

This shift system is one way to work with a new situation, yet it comes with challenges. For example, in the second shift, late in the day and already shorter than the morning shift, teachers and students are tired. They have less time devoted to teaching and learning—and infrastructure is already stretched thin. Consequently, these factors make it hard to learn.

Q: So are “multiple shifts” the prevailing model for refugee education?

A: No, the shift model is one of four models we have identified. Until five years ago, the norm was separate schools for refugees, with educational goals focused on preparing refugee students to return to their countries of origin. That first model, which still exists, was also influenced by the proliferation of refugee camps, where refugees were physically separated from national populations.

But more recently, there has been a massive increase in the number of countries where refugees have access to national school systems—including following the same curriculum, with national teachers, in the national language of instruction, and with national certification. Now twenty of the twenty-five largest refugee-hosting countries provide some access for refugees to national education systems.

It is within this approach of integrating refugees into national education systems that we find the three other models of refugee schooling. One in which refugees are studying together in the same classrooms, which is the case in some parts of Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, and Turkey, for example; another in which refugees use the national model of education, teachers, curriculum, exams, but are physically isolated from national students because they are in camps, such as for most refugees in Kenya, Pakistan, and Ethiopia; the final model is where refugees and nationals share the same school buildings but attend class during a “second shift,” as in Lebanon.

Q: Is integration the best way to educate refugees?

A: Just like for all populations, there is not one “right” kind of education. One of the major challenges of integration is that often the schools that refugees integrate into are of quite poor quality. Only one-third of Lebanese nationals chose public schools, and those with the means to do so opt out for options they perceive as of better quality. Across countries, we see refugees accessing primarily lower-quality public education, just as marginalized national populations do—this is true in the United States as well. Integration also creates both challenges and opportunities for social inclusion and a sense of belonging for refugees—and nationals. The model where refugees and nationals are in class together creates possibilities for developing relationships among them, but these relationships are challenging to build, especially in settings where there is broader social exclusion, poverty, and marginalization for refugees and the nationals with whom they are in class. Many teachers have described to us wishing they had the training and skills to help them foster these relationships in ways that are deep, productive, and authentic.

There is also the challenge of what refugees can do with an education they receive in an integration model. In most countries, refugees cannot access rights that would enable them to work or to own property. Education for multiple futures—the kinds of navigational capacities we discussed—could help refugees to keep their options open, but no matter what kind of education they access, opportunities for refugee graduates to further their studies or create livelihoods most often still depends on the restrictions that nation-states impose on them.

Q: What have you found, in the course of your research, that gives you hope for the future?

A: We are in a moment of crisis that demands shared responsibility and creativity. To imagine that one in four individuals in Lebanon is a refugee, to imagine that one million South Sudanese refugees have entered Uganda over the past year, or that currently 700,000 Venezuelans are fleeing into Colombia and Brazil—this rapid shift in population is inconceivable to someone sitting in Cambridge. Our research is leading us to re-envision the kinds of pathways that young people may chart in order to build their future livelihoods that depend less on opportunities in a geographical location and more on transnational possibilities. In research funded by the Weatherhead Center, we found that Somali refugees have created local and global networks of resources and relationships that enable success in school (this research recently won a top award in educational research). There is a great deal of uncertainty in these pathways, given the lack of rights and tenuous access to social services. Yet young refugees are trailblazers of these pathways and we hope to continue learning from them about the kinds of education that indeed prepares them for multiple futures.

—Michelle Nicholasen, Communications Specialist, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs

Faculty Associate Sarah Dryden-Peterson is an associate professor of education at Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research interests include comparative education; community development; education in armed conflict, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa; migration; and transnationalism.

Captions

1. First-graders in a non-formal school in Lebanon build a topical relief map. Credit: Elizabeth Adelman

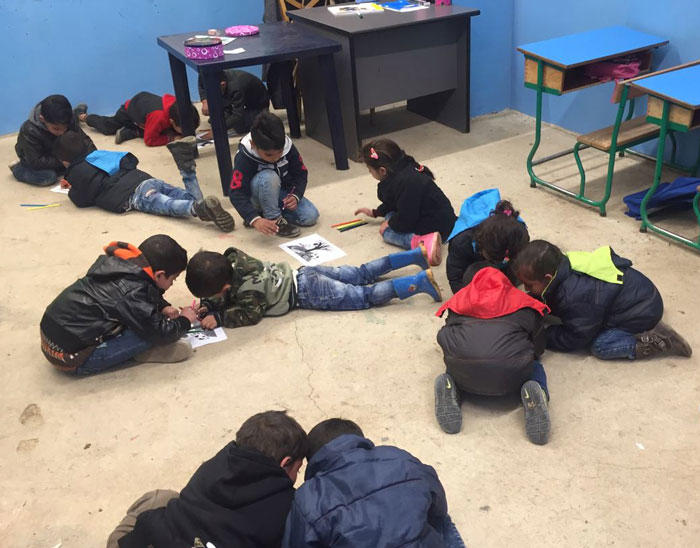

2. Second-graders in a non-formal school in Lebanon color tiles for a group story creation. Credit: Elizabeth Adelman