It’s an argument we’ve heard before: governments should not negotiate with terrorist organizations that engage in violent activity. This idea is pervasive throughout the academic and policy worlds, but what about public opinion? Do citizens think the government should shun social movements that adopt extreme tactics often associated with terrorist organizations?

Social protest takes various forms, and organized social movements have various intentions—from benign disruption to purposeful violence. In their forthcoming paper for Comparative Political Studies, Connor Huff and Dominika Kruszewska look at how the tactical choices of social movements affect public opinion about whether or not—and to what degree—governments should negotiate with social movements.1

In research involving 2,000 Polish citizens, Huff and Kruszewska document what many already believe: people were approximately 30% less likely to support government negotiations with organizations that use bombs compared with occupations. “Our results show that public support decreases for both separatist organizations and social movements that adopt bombing as a tactic when compared against occupations and demonstrations,” they write. The researchers find mixed support for whether respondents think organizations that use bombings should receive fewer concessions once negotiations begin.

“Given that a wide range of social movements emerging around the world are making similar tactical choices, we hope to provide a framework from which researchers can continue to explore how the tactical choices of both violent and nonviolent movements affect public opinion about their organization and goals.” —Huff and Kruszewska

While the study focuses on a single nation, the researchers believe the findings are generalizable to other countries. “Our findings are likely to be most relevant when we observe either nascent organizations or issue areas on which the public does not have consolidated views,” they write.

Experimental Design

The researchers use an experimental survey design and randomization scheme to test competing hypotheses about how varying degrees of protest tactics—including demonstrations, occupations, and bombings—influence public opinion.

Huff and Kruszewska chose these three tactics because they form an obvious scale of intensity that fits with the theories presented in their paper: the benefits of extremeness, moderation, and no concessions. Each tactic has also been used in recent years by movements actively pursuing independence. And, these tactics are typically premeditated rather than spontaneous. Accordingly, the researchers excluded a range of “spontaneous” violent activities, such as throwing Molotov cocktails, damaging property, and rioting.

COMPETING THEORIES ABOUT HOW

|

| Theory One: The Benefits of Extremism |

|

The first theory, explored primarily through the study of strikes and urban riots, posits that disruptive and violent tactics increase public support for a movement. Violent tactics bring attention to the movement as a “legitimate claimant to an issue” by signaling commitment to the political cause.2 |

|

Hypothesis 1A: The more extreme the tactic, the more respondents believe that the government should negotiate with the movement. Hypothesis 1B: The more extreme the tactic, the more respondents believe that the government should concede to the movement during negotiations. |

| Theory Two: The Benefits of Moderation |

|

The second theory argues that moderation and nonviolence increase public support for the movement. Nonviolence provides a “moral advantage” to the social movement, strengthening domestic and international legitimacy.3 |

|

Hypothesis 2A: The more extreme the tactic, the less respondents believe that the government should negotiate with the movement. Hypothesis 2B: The more extreme the tactic, the less respondents believe that the government should concede to the movement during negotiations. |

| Theory Three: A "No Concessions" Policy |

|

The third theory builds on the idea that governments should adopt a strict policy of “no concessions” when negotiating with terrorist organizations. Refusing to give in to the demands of groups that adopt the most extreme tactics discourages this type of violence.4 |

|

Hypothesis 3A: When organizations adopt bombing as a tactic, respondents are less likely to believe that the government should negotiate with the movement relative to other possible tactics. Hypothesis 3B: When organizations adopt bombing as a tactic, respondents are less likely to believe that the government should make concessions to the movement during negotiation relative to other possible tactics. |

Huff and Kruszewska write, “Demonstrations are one of the most common forms of contentious political activity in democracies and, if registered with the authorities, they are legal,” which is why they are the baseline tactic for this research paper.

How does public perception of violence influence public support for government negotiations with separatist groups or other social movements?

To find out, the researchers partnered with one of the oldest public opinion survey groups in Poland. The interviewers administered computer-assisted surveys in person to a nationally representative sample of approximately 2,000 Polish adults. Respondents were sampled using random-quota sampling.

The researchers chose Poland because its citizens are less likely to have strong opinions about how the government should respond to organizations that conduct occupations or use bombs. This is in contrast to the United States, with the recent Occupy movement, and the United Kingdom, with its enduring history of conflict with the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Tactical Choice, Public Opinion, and Government Bargaining

Half a million Catalans marching through Barcelona, Spain, adorned in their region’s red and yellow. Pro-Russian protesters occupying government buildings in Donetsk, Ukraine. Renewed bombing by the New Irish Republican Army (IRA) in Northern Ireland. These recent examples of contentious political activity captured public attention not only for why they were protesting, but how. Together, these dual political strategies—why social movements protest and how—have helped shape whether some of the most iconic social movements in history succeeded or failed.

Social movements force governments to make a number of decisions including whether to repress or engage with a movement, and if so, how much to concede. How governments respond at each stage can have long-term electoral ramifications. Huff and Kruszewska focus on two critical junctures in the strategic decision making of governments—whether to negotiate and how much to concede in bargaining—when public opinion is likely to be particularly important to the leaders of democratic governments.

One of the tricky issues about empirical tests of protest tactics is that people might sympathize with a movement’s political goals. “We take care to avoid situations in which respondents rely on easily accessible frames about prominent tactics or issue areas which might lead respondents to attribute the tactic they are assigned through treatment to a familiar organization,” write Huff and Kruszewska. Respondents also answered open-ended questions, which the researchers analyzed using a cutting-edge text-analysis tool, Structural Topic Model (STM).5

Although the internal and external factors influencing social movements’ tactical decisions have been studied extensively, the effects of these choices on public opinion are underexplored. “The use of an experimental design makes an empirical contribution to a field that has relied mainly on observational and qualitative data,” they write.

Huff and Kruszewska conclude that further research could explore whether their findings hold across a range of violent tactics, or whether there is something unique about the use of bombings that invokes the idea that the movement is a terrorist organization.

—Amanda Pearson (@Pearson_ink), Communications Specialist, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.

Connor Huff is a Graduate Student Affiliate at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. He and Dominika Kruszewska are both PhD candidates in the Department of Government at Harvard University. This blog post is based on the following journal article:

Huff, Connor, and Dominika Kruszewska. "Banners, Barricades, and Bombs: The Tactical Choices of Social Movements and Public Opinion." Comparative Political Studies. Published electronically January 14, 2016. doi: 10.1177/0010414015621072.

Footnotes

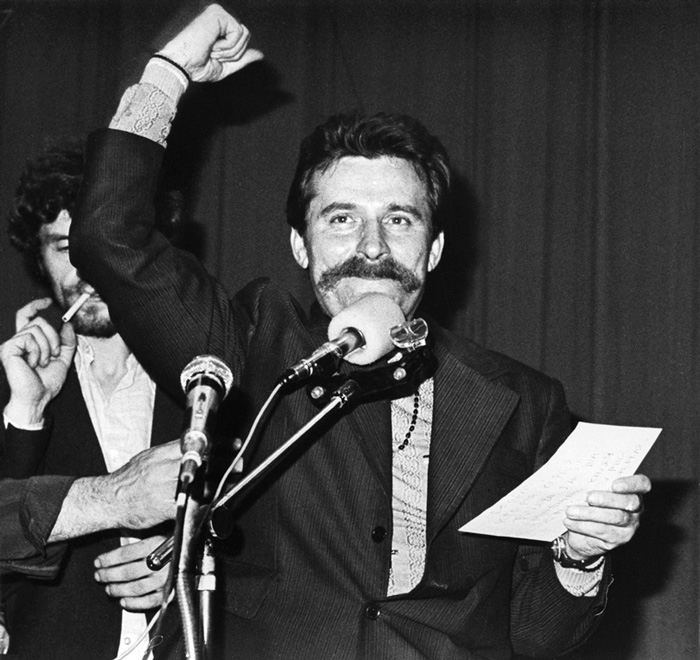

- Many social movements know that their tactical choices influence both potential government action and public opinion. During the Solidarity protests in 1980s Poland, the Strike Committee imposed a strict ban on alcohol to ensure discipline and peaceful protest at the Lenin Shipyard. And the Spanish indignados occupying Puerta del Sol in Madrid patrolled the tent city to prevent violence and vandalism.

- Astin, Astin, Bayer, & Bisconti, 1975; Bloom, 2004; Bueno de Mesquita & Dickson, 2007; Gamson, 1975; Giugni, 1998; McAdam, 1983; Pape, 2003; Shorter & Tilly, 1974; Tarrow & Tollefson, 1994; Thomas, 2014.

- Abrahms, 2012; Abrahms, 2013; Sharp, 1973; Shaykhutdinov, 2010; Stephan and Chenoweth, 2008.

- Chellaney, 2006; Clutterbuck, 1992; Netanyahu, 1986.

- To learn more about the Structural Topic Model, the April 2016 virtual issue of Political Analysis includes the paper “Computer-Assisted Text Analysis for Comparative Politics” by Weatherhead Center Faculty Associate Dustin Tingley, et al.

Photo credits: Olmo Calvo, Democracia Real YA demonstration held in Madrid, Spain on May 15, 2011, Wikimedia Commons; Lech Wałęsa, strike at the Vladimir Lenin Shipyard in August 1980, Wikimedia Commons; a scene of devastation on a main street in Omagh, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland following a Real Irish Republican Army car bombing on August 15, 1998. © Daily Mail/Rex/Alamy Stock Photo.