Respecting the rights and distinct cultures of ethnic minorities was one of the Chinese Communist Party’s founding principles. But a recent Party document signals that assimilation is the new rule.

By Aaron Glasserman

Last November, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party passed a “resolution on history.” It tells Party officials and the Chinese people how they should talk, teach, and write about the first century of the Party’s history: the accomplishments to be celebrated, the lessons to be learned, and the examples to be followed. The resolution, just the third of its kind since the Party was founded in 1921, enshrines Xi Jinping’s position in the Party pantheon alongside Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping and affirms the wisdom and effectiveness his agenda—from cracking down on corruption and developing China’s military capacity to handling the COVID-19 pandemic and reasserting the Party’s dominance over society and the market.

The resolution also endorses the Party’s current approach to what it calls “nationalities work” or “ethnic affairs”—essentially, how it governs China’s fifty-five officially recognized minority nationalities and their relationships to one another and to the Han majority, which makes up about 91 percent of the total population. Since 2017, this approach has involved the mass internment of Uyghurs and other Muslim peoples in Xinjiang, an autonomous region of China that is home to many minority groups. This approach also involves a drive to “China-ify” all religion, including Islam and Tibetan Buddhism, and endorses new restrictions on the use of languages other than standard Mandarin in Inner Mongolia and other regions where minority nationalities are concentrated.

The new approach is assimilationist and emphasizes the blending of ethnic differences. The goal is not just to strengthen citizens’ sense of belonging to a larger, unified Chinese nation under the Party but also to mute expression of other—in the Party’s view, competing—identities.

The resolution refers to following a “correct and uniquely Chinese path to dealing with ethnic affairs.” A recent article in one of the Party’s top journals explains the main points of this vague formulation, which includes the need to “promote extensive contact, interaction, and blending among different nationalities.”

Talk of “blending” became more common in official and academic circles in the early 2010s as part of a larger, surprisingly public debate on the merits of promoting a single Chinese identity over individual ethnic identities. The new historical resolution’s allusion to blending through the phrase “uniquely Chinese correct path” suggests that it is no longer a topic of debate and has become a tenet of ideology.

The term “blending” (jiaorong) and its assimilationist connotation contrast sharply with earlier, foundational principles of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which included respect for minority nationalities’ rights and autonomy. This autonomy and the freedom to use their own languages and “maintain or reform their own customs” were guaranteed in the 1954 and 1982 constitutions of the People’s Republic of China.

The CCP has traditionally presented itself as the guarantor of minority nationalities’ rights, and since the 1950s has attempted to deliver on that promise with a complex system of ethnic classification, autonomous areas, and affirmative action. For example, every citizen has their ethnic identity indicated on their national ID, and members of minority groups may receive extra points on the gaokao—China’s massive and notoriously grueling college entrance examination. Minorities have also been exempt from various restrictions, including the One Child Policy (which was lifted for all citizens in 2015) and mandatory cremation—an issue of particular concern to practicing Muslims, for whom burial is an important religious duty.

The Party’s stated commitment to respecting minority nationalities dates back even to its formative years in the 1930s and 1940s, before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. Back then, the CCP was an insurgent force trying to foment revolution against the ruling Nationalist Party (which would later retreat to Taiwan) while also liberating China from the Empire of Japan. Both the Nationalists and the Communists faced a basic challenge: how to hold on to the vast territory that had been controlled by China’s last dynasty while also winning loyalty and support from the diverse peoples who inhabited it. The Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek asserted that there was a single Chinese nation, and that all the peoples within China belonged to it. By contrast, the Communists claimed that China was a “multiethnic country” and promised recognition and autonomy to all minority peoples. The Communists also embraced the idea of a single, overarching “Chinese nation” but maintained that the various ethnic groups within China were equal and distinct elements within it.

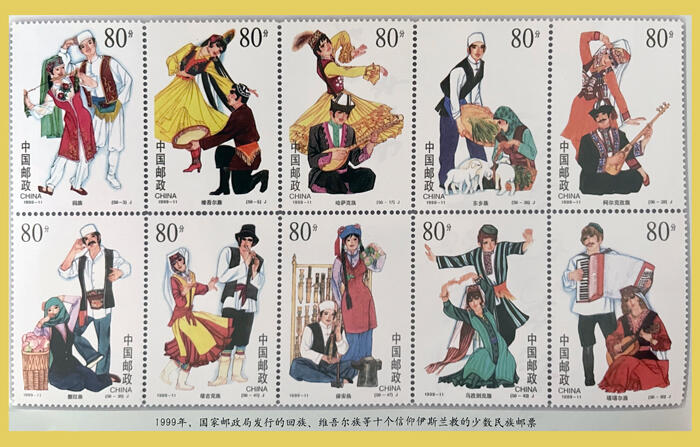

To be sure, there have always been limits on the autonomy that minority nationalities actually enjoy and the extent to which people in the PRC are allowed to express cultural differences. State-sponsored arts festivals and performances typically feature representatives from different minorities as well as the Han majority. As China scholar Emily Wilcox has shown, in the early years of the PRC, the government used these occasions to promote a new multiculturalism and present an image of a strong, unified country. But such celebrations of difference can also be highly stereotyped. Anthropologist Dru Gladney (see for example his 2003 book, Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects) and others have documented how minorities represented in media are often exoticized, feminized, and eroticized. The smiling, dancing minority holding a musical instrument has become a trope.

At least until recently, the most repressive period of PRC ethnic policy was the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. Minority rights were widely disregarded, and any sort of identity not oriented toward then-President Mao Zedong was fiercely criticized and often violently attacked. But the CCP would later express regret over this violation, in no less significant a document than the previous historical resolution, passed in 1981 under Deng Xiaoping. As that resolution stated: “In the past, particularly during the ‘cultural revolution’, we made a grave mistake on the question of nationalities… In our work among them, we did not show due respect for their right to autonomy. We must never forget this lesson.”

Now, thirty years later, the Party is again looking back on its history to chart its path forward. This time, however, the recent past seems to be a source of confidence rather than regret. The new resolution does mention “regional ethnic autonomy” but also specifies that the Party has “upheld and improved” this system (emphasis added)—potentially facilitating justification of more changes in the future.

The way the CCP talks about “blending” minority nationalities today is strikingly similar to what it used to accuse the Nationalist Party of arguing. The recent article in the Party theory journal mentioned above defines “more than five thousand years of Chinese history” as “a history of contact, interaction, and blending among different nationalities.” Compare this to an article on ethnic affairs published in 1954 in the People’s Daily, a CCP-controlled newspaper, that condemned the Nationalist Party for insisting that the Chinese nation developed out of multiple peoples “mixing” (ronghe) together.

What is behind this apparent shift toward assimilationist policy? After the collapse of the Soviet Union, CCP resolved to avoid the mistakes of its northern neighbor—mistakes that included, in its view, a loss of control over peripheral territories inhabited largely by ethnic minorities. Decades of sporadic unrest in Xinjiang and Tibet seemed to confirm the need for control at all costs, even if the unrest itself was at least in part a response to the regime’s draconian policies. And when China’s leaders looked abroad, they did not need to strain their vision to find examples of disorder and conflict rooted in or exacerbated by ethnic tensions, from the wars in the Balkans to the Kurdish insurgency in Turkey. At the same time, the world today offers many models of strongman demagogues strengthening their grip on power by promoting exclusionary and chauvinist nationalism that leaves little room for diversity.

Prominent Chinese intellectuals have also identified advantages of assimilationist policy in their interpretations of United States history. The historian Xu Jilin, for example, sees the power of the American system as a function of social cohesion. This cohesion, in his view, has been maintained by the historic dominance of Anglo-Saxon culture, as well as the ability of immigrants from all over the world to accept it. Xu also believes that identity politics and the renewed salience of race and ethnicity in American political culture threaten this cohesion.

Of course, there is no reason we should have expected the same policies to remain in place indefinitely. The regime’s endurance is in part a function of its adaptability. If it can compromise on socialism, it can compromise on multiculturalism. The CCP now occupies a radically different position on the world stage than it did even in the 1980s, let alone the 1940s. Today, the Party is not an insurgent, but a hegemon. The priority is controlling the population, not mobilizing it for revolution. Moreover, other powers have done little to push back against the regime’s violations of minority rights and gross human rights violations in Xinjiang. The limited “diplomatic boycott” of this month’s Beijing Winter Olympics by the United States and a handful of other states is a case in point.

This historical resolution marks a new period in the history of the CCP. It has widely been seen as paving the way for Xi Jinping to serve for a third term, and perhaps indefinitely, breaking with the precedent established by Deng Xiaoping. It may also signal a new, overtly assimilationist phase in the Party’s approach to “ethnic affairs” and a rejection of its foundational commitment to recognizing and respecting ethnic differences. If this is the case, we should expect an intensification and expansion of the already brutal crackdown on language use, cultural expression, and religious practice already underway in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia.

Contributor Bio

Aaron Glasserman is an Academy Scholar with The Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. He received his PhD in the Department of History at Columbia University in 2021. His research focuses on the history and politics of ethnicity and religion in China.

Captions

- Korla: Uyghur musicians hired to promote new year's sale, January 1, 2006. Credit: cce, Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

- Photograph of Chinese commemorative stamps. Top row, from left to right: Hui, Uyghur, Kazakh, Dongxiang, Kyrghyz. Bottom row, from left to right: Salar, Tajik, Baoan, Uzbek, Tatar. Photo credit: Aaron Glasserman

- Rare Visit to Ancient Kashgar Reveals Uyghur “Ghost Town” | In a viral video, a Taiwan tourist expresses his feelings about China’s high-tech repression in the Uyghur region. Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service director Alim Seytoff discusses the video. Credit: Radio Free Asia, YouTube