Four scholars contextualize India’s controversial citizenship amendments within the history of imperial rule, mobility, and itinerancy in South Asia.

By Swati Chawla, Jessica Namakkal, Kalyani Ramnath, Lydia Walker

In the second week of December 2019, protests over changes to India’s citizenship legislation made the front page of three major US newspapers—the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. In the time since, the protests have continued unabated all across India and abroad, in big cities and small towns, on university campuses and in front of town halls. They have held the world’s attention. At the heart of these protests is the question: Who is a “citizen” in India today? In this essay, four scholars of citizenship draw on their ongoing archival and on-site research to illustrate why the answers to that question lie within the histories of imperial rule, mobility, and itinerancy in South Asia.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), signed into law on December 12, 2019, redefines access to Indian citizenship on ethnoreligious grounds by providing a fast-track to Indian citizenship for Hindus, Parsis, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan (but not Nepal, Sri Lanka, or Myanmar), while leaving out Muslims from these countries. Critics of the CAA invoke the historical legacy of the India-Pakistan partition in 1947 and the extreme dangers of using religion as a basis for citizenship, which led India’s original Constitution makers to adopt a territorial—rather than lineage-based—definition of citizenship. Legal experts have pointed out that the exclusion of minorities in other neighboring countries that have a track record of persecution—notably that of the Rohingya in Myanmar, the Tamils in Sri Lanka, or the Buddhists in the Tibetan Autonomous Region—are proof that the CAA violates the right to equality enshrined in the Indian Constitution, available to citizens and noncitizens alike, because it makes arbitrary classifications based on place of origin and religious affiliation.

Closely connected to the CAA is the National Registry of Citizens (NRC), a labyrinthine bureaucratic process carried out in India’s northeastern state, Assam, from 2013 to August 2019 to identify “foreigners” and deport them. Forcing people to produce documentary proof of belonging going back several generations, the NRC relies on voter lists where “doubtful” voters are identified. Those without sufficient paperwork proving their long, uninterrupted presence within the territorial boundaries of the Indian state were left out of the registry. They were then compelled to make counterclaims before “foreigners’ tribunals,” notorious for their lack of procedural or substantive standards. The determinations by the tribunals have torn families apart, even resulting in multiple instances where people have killed themselves out of despair. Shortly after the passage of the CAA, the Indian Minister of Home Affairs, Amit Shah, who presented the government’s defense of the CAA to both houses of Parliament, declared that the NRC would be extended beyond Assam to the whole country. In the wake of the protests and widespread criticism, Prime Minister Narendra Modi denied this on December 22. But many were not convinced, and protests across the country have continued unabated.

The accounts that follow, based on archival and on-site research by four scholars of citizenship, show how the CAA and NRC (along with the National Population Register, or NPR) are legislative and administrative techniques intended to rid the country of people deemed “undesirable” in the current political climate. Citizenship in India was never only an “internal matter,” as the Indian government has repeatedly claimed. It was, and continues to be, shaped by regional histories and the exigencies of empires.

To understand who counts as Indian today, we draw upon histories of imperial rule, mobility, and itinerancy in South Asia and highlight four areas of exclusion that the citizenship amendments raise: the exception of regions in northeastern India from the operation of the CAA; the practices of registration and enumeration that the NRC employs; the exclusion of communities like the Buddhists from the Tibetan Autonomous Region from the language of the CAA; and historical (im)possibilities, drawing on the example of French Indians, of choosing alternatives to Indian citizenship.

The Northeast Exceptions

by Lydia Walker

The ninety-one-year-old critic of the Congress government, J.B. Kripalani, was interviewed by the Indian Express in June 1980 about the possibility of a National Registry of Citizens (NRC) for Assam, where he argued that stripping citizenship from foreign nationals was “the only viable solution.” He warned that “the situation is grave and has international dimensions,” and that if nothing was done immediately on the issues of citizenship and migration in Assam, as well as the question of “the tribals” in neighboring states, “the entire northeastern region might start demanding secession from India.”

The northeast (which currently includes the eight Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura) had been made into an Indian periphery by three partitions—that of Burma from India in 1937, that of East Pakistan from India a decade later, and that of Bangladesh from (West) Pakistan in 1971. Each of these divisions cut through communities creating citizens and refugees, sometimes in the same person at different historical moments. A colleague’s grandfather had a theater troupe that toured villages between Bengal and Assam until the partition of 1947 severed their routes. He remained in what had become East Pakistan until seeking refuge in West Bengal in 1971, then shifted to Shillong in the Khasi Hills of what is now Meghalaya, before settling in Siliguri, in the land corridor that forms the thin connective tissue between “mainland” India and the northeast. This story of regional mobility and its constraints is one of many such journeys that an NRC sought to regulate and codify out of existence.

Unsurprisingly given the region’s history, when an NRC for Assam was implemented in 2013 and the final list was released this past August, it “caught” too many people the central government considered appropriately Indian—of the nearly two million inhabitants of Assam who could not prove citizenship, a significant portion were Hindus. The results of the NRC in Assam, and the promise to extend the process to the rest of India, spurred the Indian government to reintroduce the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) upon which it had campaigned in the last two elections. When the CAB had been first introduced in 2016, it was withdrawn in part due to protest from northeastern regions.

While the Citizenship Amendment Act and National Registry of Citizens are two separate legal processes, from the perspective of certain communities in northeastern states, they both exacerbate long-term tensions, in a region with its own fraught relationship with the Indian state. The linking of these issues explains the northeast carve-outs in the CAA, which extended the colonial-era Inner Line of protected land ownership in order to bring certain northeastern leaders on board who had refused to support the bill in 2016. These exceptions continue the original colonial practice of “protecting” certain communities in the region in such a way that demonstrates their liminal relationship to the Indian state, while those protections are often paper thin in actuality.

Practices of Citizenship Registration

by Kalyani Ramnath

The bureaucratic practices that underlie the CAB and the NRC have echoes in debates that South Asian governments (India, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar) had in the final years of colonial rule and early years of independence: how to square emigration, nationality, and citizenship in a regional and diasporic context. These debates, which took place in the 1940s, were prompted by Indians who emigrated (and were forced to emigrate) to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Burma (present-day Myanmar) during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many of them as laborers on plantations and paddy fields that funded imperial rule. Many political leaders in Sri Lanka and Burma voiced fears of outsiders taking over lucrative government employment or buying up tracts of land that had historically belonged to long-time residents. At the time, the British Indian government proposed immigration agreements, intended to regulate the flow of capital and labor between India and other parts of Asia (Burma, Ceylon, Malaya) and Africa (Kenya, South Africa). They were never brought into force, interrupted by the exigencies of World War II. When the war ended and India, Burma, and Sri Lanka gained independence, former migrants became new minorities.

The practices of enumeration, identification, and registration that were proposed in the immigration agreements in the early 1940s carried over into postcolonial South Asia. Nationalist leaders continued to fan the flames, extolling the dangers of uncontrolled emigration. Colonial-era regimes of mobility and residence were heavily restricted. In the wake of World War II, permits and passes—rather than passports—were introduced to deal with the Indian “evacuees” from Burma to return to their homes in Burma. The Palk Strait that divided the Indian mainland from the island of Sri Lanka was heavily patrolled, rumors flying fast and thick that there was a robust trade in ration cards and birth certificates for Indian-origin migrants to legally “prove” citizenship in Sri Lanka. Newspapers wrote of “sly comers” and “illegal” immigrants. In Sri Lanka, trade unions and politicians strongly protested the heavy burden of proof in the context of citizenship by registration/naturalization legislation: how was an ordinary emigrant supposed to produce documentary proof of residence going back three generations? Similarly in Burma, Indian traders and businessmen attempting to return despaired that it had become impossible to return “home.” They claimed that the system of temporary permits that Burma put in place for return migrants did not recognize the capital they had invested in Burma’s economic prosperity.

These bureaucratic practices leached into contestations over legal citizenship and identity (religious, ethnic, racial), and continued well into the twentieth century. For example, nearly 700,000 people, many of them plantation workers forced to emigrate from India to Ceylon, applied for Ceylonese citizenship under the 1949 naturalization legislation. After lengthy enquiries by citizenship commissions lasting more than a decade, only about 10 percent finally took oaths as Ceylonese citizens. Between India’s citizenship legislation in transition and Ceylon’s decision to verify citizenship by registration, hundreds of thousands have been left stateless. Between the 1950s and 2003, multiple repatriation agreements were signed between the two governments, sending some to “homes” in India where they had never been. It was only legally resolved in 2003 when Sri Lanka granted citizenship to any remaining applicants.

Similarly, in Burma, the military takeover of civilian government in 1962 led to massive expulsion of Indian migrants, documented and otherwise. Only those listed under “national races” in a 1982 legislation were counted as citizens. Those that were not, including notably the Rohingya, were left out.

When people excluded from the NRC make similar claims (that documentary proof of the sort that the NRC demands is practically impossible to produce, that traveling and appearing before foreigners’ tribunals is expensive and beyond their reach, that the whole exercise is futile since India is their only home), they have been systematically delegitimized, their fears branded groundless. Placing people in legal limbo—unsure whether their documents would be accepted, uncertain about how long they would be allowed to stay—has a dark and dangerous historical legacy in South Asia.

The Impossibility of Renunciation

by Swati Chawla

An important criticism of the CAA has been made on the grounds that it makes no mention of persecuted minorities from Sri Lanka and Myanmar. Among those in opposition to the bill, a few also mentioned the 94,000-strong population of Tibetans living in exile in India following His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s escape into India in March 1959, who also face the threat of religious persecution in the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

While a path to citizenship has largely been unavailable to Tibetans who came after 1959, many who arrived in the preceding decades were already on their way to being naturalized as Indian citizens at that time. Indeed, the Dalai Lama had himself followed in the path of many Tibetans who had been coming—as traders and pilgrims, monastics and laity—to parts of northern and northeastern India for centuries. Tibetans could enter British India without a passport, visa, or any entry permit—with Indians traveling into Tibet enjoying reciprocal provisions.

As the newly founded Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China began to consolidate their borders in the 1950s, they also grew increasingly suspicious of customarily itinerant borderland populations. Records from the Citizenship Section of the Home Ministry reveal how a seemingly straightforward requirement in their application for citizenship became a tragic reminder for Tibetans of their statelessness after the failed uprising against the Chinese in 1959. In order to be accepted as Indian citizens, applicants had to furnish evidence of having renounced their former nationality before a competent authority of that country. Hence, not only did the authorities have to ascertain a firm place of origin—which was especially difficult for customarily itinerant populations such as monastics and traders—but they also unwittingly required that applicants produce a renunciation certificate from the very regime they had fled.

This left Tibetans in India with no choice except to identify (even temporarily) as Chinese nationals and apply to a Chinese Consulate for the certificate, something many were, in principle, opposed to doing. They pleaded that they had never been Chinese, and should be allowed to renounce their Tibetan nationality. The Indian authorities argued that Tibet no longer existed independent of China. Owing to a large number of such applicants, they were forced to make a concession. In the application of a Tibetan Buddhist monk that came to be widely applied as a precedent for others, the Citizenship Section noted in 1956 that a personal declaration regarding renunciation of the other nationality could be considered sufficient in such cases. The summary rejection of citizen applications by itinerant Tibetans, such as Buddihist monastics, underscores the bureaucratic suspicion of borderland populations who were customarily on the move in the decades immediately after Indian independence.

Alternatives to Indian Citizenship?

by Jessica Namakkal

In 1937, Reginald Schomberg, the British Consul General in Pondicherry (French India), wrote in a report that in and around the French Indian territories “the nationalities are hopelessly mixed up, and many persons do not know, and cannot prove, whether they are French or British subjects.” France, which formally possessed five territories in India beginning in the early nineteenth century and lasting until 1962, had allowed people in French India to become French citizens beginning in the 1870s. As anticolonial (anti-British) organizing intensified in the early twentieth century, French India became a refuge for freedom fighters fleeing British persecution. Famed Bengali nationalist Sri Aurobindo Ghosh arrived in Pondicherry in 1910 and spent his entire life in the French territory. Tamil revolutionaries C. Subramania Bharati, V.V.S. Aiyer, and V. Ramaswamy Iyengar all spent time in Pondicherry in the 1910s and 1920s, staying out of the jurisdiction of British colonial police. It became a common practice for those involved in anticolonial struggles to claim the right to multiple passports, British and French in this case, in order to access the ability to be mobile through differing imperial networks. Officials at both the British and French consulate often sent individuals back and forth, neither wanting to claim responsibility for the revolutionary subjects.

By 1947, when the independence of India appeared on the horizon, there were hundreds of families in the French Indian territories who had been French citizens for multiple generations. Why, they asked, should they give that up to join a newly emerging nation, one that many saw as devoted to a national identity (Hindi speaking and casteist) that seemed more foreign than the French identity they had already adopted? Though many in French India did take up the cause of anticolonial, anti-French campaigning, which succeeded in 1954 when France agreed to leave, there were significant numbers of people who viewed the practice of French citizenship as a tool of protest against a central government that did not have their interests in mind.

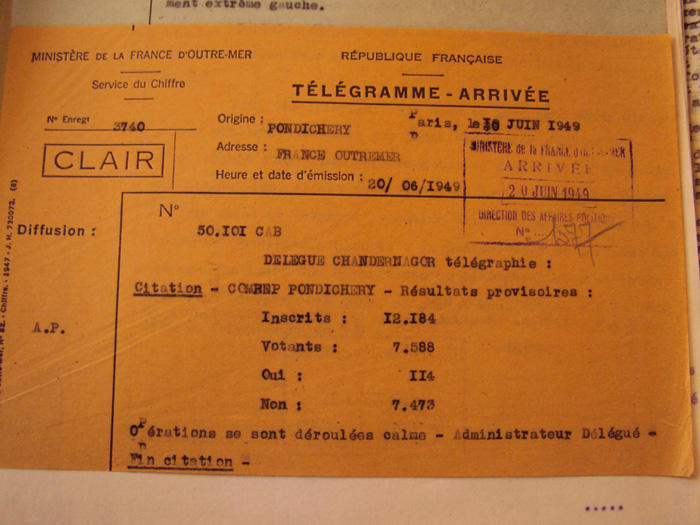

Today, there are almost 5,000 French citizens who live in Puducherry (the name changed in 2006). These French citizens are also Tamil, sharing language, cultures, customs, and history with the Indian citizens who live around them in Puducherry and the surrounding areas of Tamil Nadu. Yet, they vote in French elections at the local French consulate in Puducherry, and many speak French and send their children to French schools. Because India does not allow dual citizenship, they hold French passports only, though it is often the case that they cannot afford to travel to France. Many of the French Tamilians are Catholics, while some remain Hindu or Muslim. Some French Indians reside in the other areas of the Union Territory of Puducherry (Mahé in Kerala, Karikal in Tamil Nadu, and Yanam in Andhra Pradesh). The fifth French Indian territory, Chandernagore, located just outside of Kolkata, voted to join the Indian Union in 1949, and thus its inhabitants were not eligible for French citizenship at the occasion of the Treaty of Cession in 1962.

Today, the majority of French Indians live in France, where they are often viewed not as French, but racialized as Indians. While it is no secret that France was not acting in the best interest of the French Indians either when they offered citizenship, as they were primarily interested in protecting the stability of the empire and and eventually postcolonial international relationships, this was mostly beside the point for those living in India. When it came to choose French or Indian citizenship in 1962, the people of French India were allowed six months to choose: if they did not go to the appropriate office with their papers proving their domicile in French India, the default would be Indian citizenship.

In the years 1947, 1962, and 1971, it was not clear for most in South Asia what the long-term consequences of holding one citizenship over another would look like (though people had many guesses). There is no doubt that some citizenships are better than others, in the sense that they allow for more and better opportunities for economic and physical mobility. Today, having the choice between two citizenships is a privilege and luxury. Further, India does not allow for dual citizenship. Against this background, granting or stripping people of citizenship is being wielded as a punitive measure. Even worse, the CAA and NRC hold people in a state of permanent uncertainty over their access and protection from states. Even as we debate these questions at a national level, it is important to remember the histories of imperial rule, mobility, and itinerancy out of which they emerged. These accounts highlight how the recent amendments—as in the instances past—are not an effort to offer refuge to persecuted minorities, but a deliberate effort to incite fear, anxiety, and obedience in the people deemed unworthy of being counted.

—Swati Chawla, Jessica Namakkal, Kalyani Ramnath, and Lydia Walker

About the Authors

Swati Chawla is assistant professor at the Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities, O.P. Jindal Global University, and a PhD candidate in history at the University of Virginia. Her current research is focused on migration and citizenship making in the Himalayan regions of postcolonial South Asia, as well as geospatial digital humanities and contemporary Buddhisms. She tweets @ChawlaSwati, and hosts the Twitter channel #himalayanhistories.

Jessica Namakkal is Assistant Professor of the Practice in International Comparative Studies and Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies at Duke University. Her book Unsettling Utopia: Decolonization, Mobility, and Borders in 20th Century French India is forthcoming with Columbia University Press. She is a coeditor at The Abusable Past and tweets @j_namakkal.

Kalyani Ramnath is a Prize Fellow in Economics, History, and Politics at Harvard University. She is a lawyer and historian, whose work focuses on migration, displacement, and citizenship in twentieth-century South Asia and the Indian Ocean world. Learn more about her work at www.kalyani-ramnath.com. She tweets @kalramnath.

Lydia Walker is a Past & Present Fellow, Institute of Historical Research, University of London. Her scholarship concentrates on post-1945 political transformation in South Asia and elsewhere as well as the role of nonstate actors and indigenous groups in international relations, religiously infused nationalisms and activisms, and definitions of sovereignty. Learn more at www.lydiawalker.info. She tweets @Lydia_Walker_.

Captions

- Public looking at a photo wall curated by the youth of Jamia Millia Islamia University at Shaheen Bagh protests, January 28, 2020. Credit: Wikimedia, (CC0 1.0)

- Front page of the Nagaland Post, December 11, 2019, highlighting protests in Nagaland and Assam as well as the extension of the Inner Line to Dimapur in Nagaland. Credit: Lydia Walker

- Passengers boarding a ferry from Dhanushkodi in India for Talaimannar in colonial Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). Credit: Kalyani Ramnath

- Billboard commemorating fifty years of exile in India from the Tibetan settlement at Bylakuppe, Karnataka in southern India. July 14, 2014. Credit: Swati Chawla

- A telegram announcing the results of the referendum in Chandernagore (a former French colony), held on June 19, 1949. Voters were asked the question “Should Chandernagore join the French Union?” Out of 12,184 registered voters, 7,473 voted “non” and 114 “oui.” Credit: Jessica Namakkal