Harvard political scientist Melani Cammett clarifies the role of sectarianism in the Syrian War.

By Melani Cammett, Faculty Associate; Harvard Academy Senior Scholar. Clarence Dillon Professor of International Affairs, Department of Government, Harvard University.

Second in a series that asks Weatherhead Center faculty to examine the dimensions shaping the Syrian conflict.

Popular discourse, especially in the West, presents the current conflict in Syria as part of an age-old struggle between the Sunni and Shi’a communities within Islam. Despite the sectarian trappings of the conflict, these divisions are not the root cause of the war in Syria. Rather, the hyperpoliticization of sectarian identities is one of the outcomes—and an increasingly salient one as conflict progresses.

The origins of the Syrian war lie in much more mundane political and economic grievances. Despite steady economic growth and an extensive public welfare infrastructure, the vast majority of the population was excluded from the fruits of development and faced thwarted aspirations for social mobility and political expression. Rising poverty rates, endemic corruption, the poor quality of social services and government repression—factors present to varying degrees elsewhere in the Middle East—constituted a critical background to the Syrian uprising, even if they do not predict precisely why and when individual protestors took to the streets.

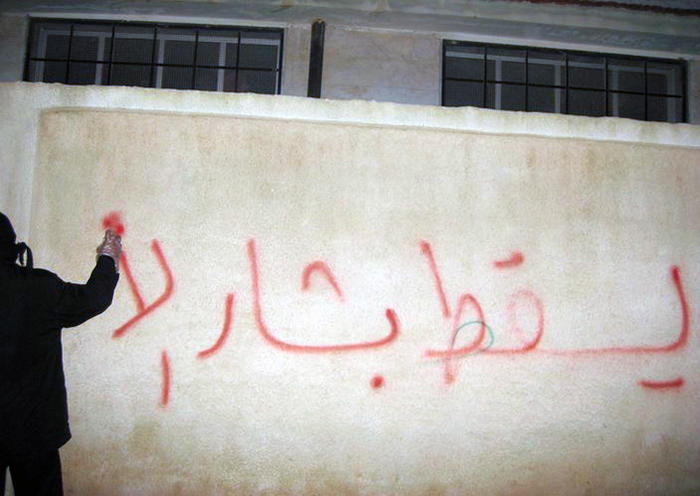

More proximately, the evolution of a peaceful uprising into a full-blown civil war was sparked by the regime’s response to the initial waves of demonstrations. On March 13, 2011, several teenagers in rural Dara’a in southern Syria spray-painted the slogan of the uprisings, al-sha’ab yurid isqat al-nizam, or “the people want the fall of the regime,” on walls in their town. Government security forces arrested the young men and tortured them, inciting peaceful demonstrations by family members calling for the boys’ release. Syrian forces then cracked down violently, spurring other protests across the country.

With the government’s refusal to address protesters’ demands and the harsh response to peaceful opposition, some opposition groups took up arms and the violence intensified. By 2013, a number of overtly Islamist groups increasingly dominated the opposition landscape, and ISIS began to move into Syria, seizing more and more territory in 2014.

Mapping the key players in the Syrian conflict is difficult due to their complexity, proliferation, and evolution over time. In broad terms, militant actors came to overpower or displace many peaceful opposition activists and groups and took over more and more territory. Some militant groups have turned their guns against each other, as witnessed by the struggles between the al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, which rebranded itself as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham in 2016 in an effort to distance itself from the al-Qaeda network and ISIS. Armed opposition groups supported by different branches of the US military and intelligence services have even started to fight each other as their zones of territorial control have become closer (Bulos, Hennigan and Bennett 2016). Thus, even groups that are formally part of the opposition to the Assad regime are at odds with each other.

Sunni-Shi’a Split

The origins of the Sunni-Shi’a split within Islam date back to the seventh century, specifically to the death of the Prophet Mohammed, the founder of Islam, in 632 AD.

One council of the prophet’s associates chose his father-in-law, Abu Bakr, to be the prophet’s successor. The supporters of Abu Bakr became Sunnis or, in Arabic, "followers of the tradition" of the prophet. The majority of Muslims around the world—about 90 percent—are Sunnis.

But another group believed that the prophet’s successor, the caliph, should be a direct descendent instead. This group supported Ali, the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law. The supporters of Ali were called the Shi’at Ali, or “followers of Ali,” and they became Shi’ites. Among predominantly Muslim countries, only Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain have Shi’ite majorities. Lebanon has a Shi’ite plurality and other countries in the Muslim world have Shi’ite minorities.

Conflict between these two groups has become bloody over the past decade. Shi’a militias have been pouring in from elsewhere in the region to defend the minority Alawi regime headed by Bashar al-Assad against violent Sunni groups, ranging from al-Qaeda to ISIS and beyond. And since 2011, vicious sectarian discourse has spiked in day-to-day interactions and in cyber-exchanges in the region. Sunni extremists refer to Alawis and Shi’as as apostates, who have turned their back on Islam and should be punished by death, while Shi’a extremists use a variety of nasty epithets to describe Sunnis—such as takfiris, or Muslims who declare another to be an infidel, and Wahhabis, to frame their opponents as followers of radical and intolerant variants of Islam (Zelin and Smyth 2014).

Misguided Views of Sectarianism

When analysts explain conflict and tensions in the Middle East in terms of sectarianism, they implicitly assume that religious differences, often rooted in doctrine and based in events that occurred centuries ago, motivate people to behave hostilely to each other and even to kill each other. This “primordialist” understanding of religious conflict implies a “pressure cooker” model of politics in the Middle East: Ethnic and religious tensions are always present, threatening to explode, but are contained by strong rulers such as Saddam Hussein or Bashar al-Assad.

But this view of sectarianism as a reflection of essential, deep-rooted differences is misguided. It assumes that religion or ethnicity are the primary foundation of people’s identities and predisposes them to conflict with members of other groups. If this is the case, however, how can we explain the decades—and even centuries—of peaceful coexistence among different groups in the region? Why do sectarian tensions become politically salient in some places but not others? What accounts for the fact that sectarian identities are not politically salient in all times—even in the same places?

As the historian Faleh Jabar has shown in his book, The Shi’ite Movement in Iraq, Iraqis in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did not primarily identify as Sunni or Shi’a, and many tribes included members of both sects. These identities only became important when policies and politicians made them important. For example, in the aftermath of the first Gulf War and during the imposition of sanctions, Iraqi state institutions began to decline; Saddam Hussein, who had presented himself as a secular ruler since he took power in 1979, increasingly turned to Islam to shore up political support. As he relied more heavily on local leaders and religious authorities to maintain control, he narrowed his support base to Sunnis, especially those from his tribe and region. The new institutions created after the overthrow of Saddam effectively institutionalized ethno-sectarianism in the political system by giving significant power to ethnic and religious actors and communities. The fact that violence was waged in the name of religion or ethnicity further cemented the importance of these social identities in Iraqi politics and society.

Instead, it is more useful to recognize that what it means to be Sunni or Shi’a, and how these identities matter in social and political life, is “constructed” by institutions and social and political practices over time. This perspective recognizes that identities have real meaning to people, but denies that they are necessarily important to people or sources of intergroup conflict in all times and places.

Sectarianism Invoked to Maintain Power

In fact, the behavior of political elites and community leaders are key drivers of sectarian conflict. When it helps to further their agendas, political leaders can whip up sectarian animosities by playing up threats to the group and convincing populations that they are the best defenders of the community. Prior to and during the course of the Syrian war, Bashar al-Assad has routinely manipulated threat perceptions to his advantage. For example, he regularly aims to shore up support by emphasizing that his downfall would lead to a takeover by extremist Islamist groups. As if to create a self-fulfilling prophecy, he reportedly released thousands of extremists from state prisons at the start of the Syrian uprising (Cordhall 2014; Sands, Vela and Maayeh 2014).

We might ask why such sectarian appeals resonate. After all, people are not naïve, and so it seems incomplete to attribute the rise of such identity-based movements purely to the actions of elites. As social psychologists have shown, targeting members of a group on the basis of their identity—whether religious, ethnic, or otherwise—is a reliable way to increase the political salience of this identity. In the current moment, Shi’a in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and elsewhere genuinely feel threatened by the rise of violent Sunni extremism across the region. Likewise, their Sunni compatriots are threatened by the rise of assertive Shi’a political movements and of armed Shi’a militias.

Sectarianism is most likely to thrive in conditions of insecurity and state weakness, and can be activated during struggles over scarce resources or political power (Davis 2005). In Syria, elsewhere in the Middle East, and in other regions, religious authorities are a key source of social order and sometimes even offer material benefits that alleviate human insecurity. This gives them a great advantage in mobilizing people when the sociopolitical conditions are right.

The transformation of the Syrian uprising into a sectarian war was a self-fulfilling prophecy. While outside analysts were quick to describe the factions in sectarian terms—even when locals and opposition groups themselves resisted such categorizations—the regime has played the sectarian narrative to its advantage from the beginning.

While opposition groups, especially in the early days, overwhelmingly called for the establishment of a secular, national Syria governed on democratic principles, Assad and his allies claimed that they were fighting a war against Islamic extremists, who wanted nothing less than the elimination of all non-Sunni Syrians. To further its goals, the regime quite directly facilitated the rise of the Islamist opposition by releasing Islamists from jails and even maintained economic ties with Islamist opposition groups, including ISIS. By bolstering a radicalized religious opposition, Assad was able to perpetuate the belief that his regime was the only logical path to stability. In doing this, he cleverly redirected US focus away from himself and toward his radical Islamic "enemies." In reality, most of the regime’s violence has been directed against opponents who do not define themselves in religious terms, such as the Free Syrian Army (although it has been greatly weakened over the years, in part due to the rise of more powerful Islamist opposition groups).

Sectarian conflict has been promoted in order to obscure the foundational reasons for the uprising. In the process, however, it has taken on a life of its own. These divisions are real to people—even when they weren’t before—particularly because they increasingly feel threatened on the basis of their membership in religious or ethnic communities (Huddy et al. 2013). In short, communal cleavages are more an outcome than a cause of the conflict.

Syrian citizens took to the streets during the Arab Spring. It was a time of protest against entrenched dictatorships in the region motivated by perceived political and economic injustices. The Syrian uprising was not a movement propelled by sectarian grievances. International players should recognize these foundational underpinnings when considering intervention or promoting policies to address the humanitarian crisis and to rebuild the country, and be cautious when dismissing the Syrian conflict as insular, sectarian, and “civil.”

During her sabbatical year, Melani Cammett is working on a variety of projects related to identity politics and service delivery in the Middle East and on a long-term project on the historical roots of economic and social development in the region. Her most recent book is Compassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in Lebanon.

Also in the “Insight on Syria” series:

- Documenting the "Burden of War" on Syrians

- The Unseen Challenges of Syrian Integration in Germany

- What are Putin's Motives?

Captions

1. People and children of two Syrian Shiite towns, Al-Fu'ah and Kafriya, attempted to set up a campaign entitled "We want bread O God" because of starvation and famine arising from blockades of food by Takfiri terrorists over two years. Photo credit: Tasnim News Agency, Fathi Nezam, 18 February 2017. Wikimedia.

2. Hundreds of thousands of protesters parade the flag of Syria and shout "Ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam" in the Assi square of Hama during the siege in July 2011. Video credit: Syrian Revolution Network, 22 July 2011. YouTube and Wikimedia.

3. The phrase "Down with Bashar" (liyaskuṭ Baššār), during the Syrian Uprising 2011. Photo credit: The Syrian Events 2011, Jan Sefti, Flickr, 12 April 2011. Wikipedia.

Key References

Clarke, Colin P. “Al Qaeda in Syria Can Change its Name but not its Stripes.” The Rand Blog. March 23, 2017.

Nabih Bulos, W.J. Hennigan and Brian Bennett, “In Syria Militias Armed by the Pentagon Fight those Armed by the CIA,” Los Angeles Times, March 27, 2016.

Simon Speakman Cordall, “How Syria’s Assad Helped Forge ISIS,” Newsweek, June 21, 2014.

Phil Sands, Justin Vela and Suha Maayeh, “Assad Regime Abetted Extremists to Subvert Peaceful Uprising says Former Intelligence Official,” The National, January 21, 2014.

Nasser et al. “Socioeconomic Roots and Impact of the Syrian Crisis.” 2013. Syrian Center for Policy Research.

Zelin, Aaron Y and Phillip Smyth. 2014. “The Vocabulary of Sectarianism.” Foreign Policy.

Jabar, Faleh A. The Shiite Movement in Iraq. London: Saqi, 2003.

Huddy, Leonie, David O. Sears and Jack S. Levy. The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Davis, Eric. 2005. “History Matters: Past as Prologue in Building Democracy in Iraq.” Foreign Policy Research Institute.