Even when her colleagues at the American University in Cairo were getting arrested and sentenced to death, sociologist Amy Austin Holmes thought she had kept herself safely under the radar. She was wrong.

By Michelle Nicholasen

It was a straightforward proposal and seemingly benign research topic. In 2016, as a newly tenured professor of sociology at the American University in Cairo (AUC), Amy Austin Holmes was thrilled to receive a grant to analyze the impact of the new, restrictive NGO law on civil society across Egypt—whose government had become increasingly autocratic under the rule of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. At the time, she had no reason to believe her work was being tracked by state intelligence.

Each of her five associates would study a different group or region of the country, with her own focus being the Nubians in the southern part of the country. She was drawn to the culture and history of the Nubians of Upper Egypt because they reminded her of the Kurds, another group that was central to her scholarship.

Descendants from an ancient civilization in the Sudan, Nubians have lived in the border area between Egypt and Sudan for thousands of years. Dam construction along the Nile forced their relocation several times in the twentieth century. Holmes knew that as an African ethnic group, the Nubians had been “Arabized” or forced to relinquish their language and indigenous identity, like some of the Kurdish groups she had studied.

Two major political developments affecting the Nubians had occurred in recent years, and she wanted to study the impact these changes had on the community.

In 2013—after a military coup removed the democratically elected Mohamed Morsi, and appointed an interim president—a new version of the constitution included an article promising Nubians the right to return to some of their traditional homeland in Egypt within ten years. It was a surprising and unprecedented gesture that hinted at a possible new period of liberalization.

And in 2016, under the presidency of military strongman Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a new law was drafted forbidding NGOs to accept foreign support, a move that would hamper civil organizations—including those that served the Nubians.

By the time Holmes embarked on her Nubian research, the climate was already fraught, since a protest law had been put into place even before the NGO law. “They made it illegal to protest…and all of these horrible things started happening. Disappearances, and the mass death sentences,” she says.

Using the grant approved by her university, in February 2017 Holmes traveled south from Cairo to Nasser El Nuba, a Nubian resettlement village, to conduct interviews. Several months after her visit, the political climate for Nubians began to heat up.

That September, Nubians in Aswan staged a peaceful protest calling for the “right of return” promised in the new constitution. In response, Egyptian security forces under President al-Sisi cracked down yet again on protesters. They detained two dozen prisoners for two months—culminating in the death of a detainee named Gamal Sorour, who had previously acted as the head of the General Nubian Union in France, a human rights organization.

“The state-controlled media accused the Nubians of being separatists,” says Holmes. “But the irony is that the Nubians are not separatists; they are asking for what’s been granted to them in the constitution.” (The Kurds in Syria, she points out, are also not asking for independence—a fact often misrepresented by the media.)

A Scholar is Labeled an “Operative”

Despite not publishing or writing anything about her visit to the Nubian resettlement village, during the following spring of 2018, news articles and television reports began to appear, referencing her visit that took place more than a year earlier. The reports—published just before al-Sisi was declared the winner of the elections—suggested Holmes was a Nubian operative, intent on internationalizing the Nubians’ cause. And she was able to pinpoint their source.

“Military intelligence wrote a report and sent it to the media outlets, who literally copied and pasted from the military intelligence report into their articles,” Holmes says. To her dismay, her home university, AUC, did nothing to publicly defend or clarify her work. So she defended herself—and called out the racist campaign against the Nubian minority in a piece she wrote for the Washington Post.

Being targeted by Egyptian state-controlled media was a shocking signal, and ultimately led to her decision to extend her stay in the United States out of concern for her safety. Holmes had secured a publication agreement for herself and all the members of her team, but after publishing two of the six articles, the project has been put on hold.

Holmes notes the irony of her situation. “I was one of the first academics to write (critical) commentary about the devastating Rabaa massacre in 2013, and nothing happened to me. Four years later I am interviewing Nubian minorities in the south of Egypt and I’m labeled an agent.” The only independent university in Egypt, AUC continues to be silent on the incident.

Challenges of Studying Minorities in the Middle East

Today, Holmes is a visiting scholar at the Weatherhead Center, working under a year-long grant to continue the research she had begun in Egypt, and is writing a book about her experiences. Her fieldwork has allowed her to see patterns across the minority groups she studies.

Today, Holmes is a visiting scholar at the Weatherhead Center, working under a year-long grant to continue the research she had begun in Egypt, and is writing a book about her experiences. Her fieldwork has allowed her to see patterns across the minority groups she studies.

“I was interested in the Nubians because I saw a lot of comparisons to the Kurdish issues I had been studying. Both groups are non-Arab minorities living in Arab countries being repressed by centralized governments and forced to ‘Arabize’” says Holmes.

But it was her interest in Nubian history and culture that brought her to the Nasser El Nuba village in the first place. “Although the displacement happened under former President Nasser, my visit there apparently attracted the attention of al-Sisi’s intelligence agents,” she says.

Holmes is all too aware of the fates of other scholars and journalists in the region. In 2015, her AUC colleague Emad Shahin was sentenced to death in a mock trial in Egypt while he was out of the country. Italian graduate student Giulio Regeni, a visiting scholar at AUC who was researching Egyptian labor unions, was tortured to death in Cairo in 2016. Several more of her colleagues at AUC have been detained or barred from coming back into the country once they leave.

Overall, her experience underscores the difficulties of studying minorities in the Middle East. “All over the region, I see the crackdown on journalists and academics as two sides of the same coin,” she says.

The Roots of Authoritarianism in the Middle East

To explain the authoritarianism sweeping the region, Holmes goes back to the birth of these nations. She believes that what began as a wave of pan-Arabism during the decolonization period eventually morphed into the autocratic states we see today in the Middle East.

“The 1950s and 1960s were the height of pan-Arabism that emphasized the homogenous nature of the newly independent states such as Egypt and Syria. It was a rejection of colonialism by saying ‘we are all one Arab people and have to be united.’ A strong military played a very important role as an institution, and that is where the autocratic governments emerge from,” she says.

Her research on the crackdown on civil society illustrates the nature of Egypt’s slide toward authoritarianism.

“The reason I find this anti-NGO law so fascinating is because I think it shows that al-Sisi is not just targeting those people who are clearly critical of the regime, but also now the groups that provide basic services, or even work to defend the government’s own laws,” she explains. “To me it says that the regime is so paranoid and afraid of independent initiatives from civil society, regardless of the political orientation, that anything that smacks of independence from the state is a threat.”

For now, Holmes will remain in the US to work on a book under contract with Oxford University Press. The tentative title is Coups and Revolutions: Mass Mobilization, the Egyptian Military, and the United States from Mubarak to Sisi. She is actively writing articles and giving talks about the semi-autonomous region of northeastern Syria that is under control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a US ally, which now holds about one-third of Syrian territory.

As part of her research in Syria, Holmes conducted a survey of members of the SDF. She has shared videos and photographs from her fieldwork on Twitter, hoping that by being transparent about her research she will avoid raising suspicions. She also aims to correct misperceptions about the region and highlight how the SDF includes both men’s and women’s units as well as Kurds, Arabs, and Syriac Christians.

Conducting research on minority groups or military issues in the Middle East is not easy, Holmes says. “Ironically, northeastern Syria—a war zone—proved a more hospitable environment for my research than Egypt. This is in part because they are now embracing the ethnic diversity of northeastern Syria. Schools in the northeast teach not just Arabic but also Kurdish and Syriac, while many signs are in mutiple languages. By contrast, Egypt continues to suppress the Nubian language—and any research on the topic.”

A Scholar's Timeline in Egypt

2011

- January: Protests erupt against President Hosni Mubarak throughout Egypt. Security forces kill hundreds of protesters.

- February: Mubarak steps down and the military takes control. Holmes witnesses the mass protests and overthrow of Mubarak.

2012

- June: Egypt holds its first free presidential elections. Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood is elected with 52 percent of the vote.

- November: Morsi appoints General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi as military commander in chief.

2013

- June: Protests erupt against Morsi’s presidency, demanding his removal amid complaints of poverty and instability.

- July: The military, led by al-Sisi, stages a coup and ousts Morsi. They arrest Morsi and other members of the Muslim Brotherhood. Adly Mansour is appointed interim president.

- August: The worst massacre in Egyptian modern history takes place at two Cairo protest camps, Rabaa and Al-Nahda. Hundreds of people protesting Morsi’s removal are shot dead by security forces. Holmes witnesses and writes about Rabaa. In September, she begins a fellowship at the Watson Institute at Brown University.

- Fall: New constitution is drafted, giving Nubians the right to return to their homelands. A new law is established, criminalizing peaceful protests.

2014

- May: General al-Sisi is elected president. Holmes turns down Harvard fellowship and goes back to American University in Cairo (AUC) to get tenure.

2016

- Fall: NGO law is drafted, preventing NGOs in Egypt from receiving foreign support. Holmes gets an external grant via AUC to study the impact of the crackdown on NGOs.

2017

- February: Holmes travels to Nubian resettlement village to conduct interviews.

- September: Nubians in Aswan stage a peaceful protest and many get arrested and imprisoned, despite merely asking for the implementation of an article in Egypt’s constitution promising a right of return to their homeland.

- November: Gamal Sorour, one of the Nubian detainees arrested in September, dies of medical neglect after falling into a diabetic coma.

2018

- April: Seven state-controlled media reports accuse Holmes of internationalizing the Nubian issue through her research and publications.

2019

- April: Although the Nubians detained in Aswan in September 2017 were released, their court case dragged on until April 2019 with little to no international media coverage. On April 7, 2019, the defendants received a suspended sentence. The decision to temporarily suspend the execution of the court's ruling can be interpreted as a way of pressuring the defendants to refrain from political activity. Meanwhile constitutional amendments are being debated that would allow al-Sisi to remain President of Egypt until 2034.

—Michelle Nicholasen, Communications Specialist, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs

Weatherhead Center Visiting Scholar Amy Austin Holmes is an associate professor of sociology at the American University in Cairo. She is also a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Captions

- Amy Austin Holmes with members of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) at a Newroz celebration on March 21, 2019 in Kobane in northern Syria. Credit: Wladimir van Wilgenburg

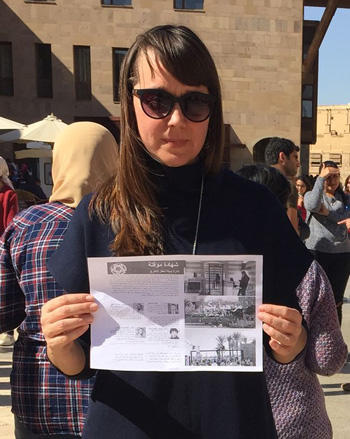

- Memorial service for Giulio Regeni at the American University in Cairo in 2016. Holmes is holding a sign of other AUC-ians who have been arrested or targeted for their research. Credit: Used with permission by Amy Austin Holmes

- Map of approximate location of Nubians and Kurds today. Credit: Kristin Caulfield

- In northern Syria, Amy Austin Holmes conducts interviews with members of the Manbij Military Council—which cooperates with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the US. Credit: Used with permission by Amy Austin Holmes