A landmark ruling in India not only decriminalizes same-sex relations but sees them as part of the natural human order. It could put into motion the reevaluation of colonial-era laws that police sexuality across the former British Empire. Professor of Women and Gender Studies Durba Mitra examines the language of the ruling in the context of the realities of being a sexual minority in India.

By Durba Mitra

“History owes LGBT people an apology.” This was the statement from Justice Indu Malhotra, who, on September 6, with four other judges of the Indian Supreme Court, declared that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (broadly known as the law against sodomy) was unconstitutional. In the days that have followed the judgment, I have wondered what it means for us to demand that history apologize for its wrongs. Indeed, the harms of history appear to be too numerous for a simple apology to the minorities consistently and historically characterized as “unnatural” or “foreign” to India by an increasingly powerful majority. To demand an apology from history for its wrongs against sexual minorities requires that we know and teach the diverse histories of sexuality for India.

Following an almost two-decade-long legal struggle to change the law, the Supreme Court’s judgment striking down 377 is remarkable. Looking over almost 500 pages of the judgment, one encounters a number of powerful interpretations of the Indian Constitution and the role of the courts in protecting minorities. Several parts of the judgment declare that “constitutional morality” must be held as a higher authority over “social morality.” But what exactly is “constitutional morality”? This phrase is likely to be defined and debated in different interpretations of this ruling in the years to come. According to an initial reading of the judgment, constitutional morality is a set of protected rights that may exceed the bounds of social norms defined by heterosexual sex and marriage. Using the language of the judgment, these rights include 1) privacy and the rights of the individual, especially with regards to consensual sexual behavior, same-sex or heterosexual, 2) the “immutable” sexual identity of LGBTQ peoples, one that is natural and normal, 3) further discussion of the meaning of “formal equality” under the constitution, and 4) the importance of dignity as a right enshrined by the constitution and to be protected by courts for the most vulnerable minorities. The judgment offers a critical apparatus to think not only rights for “sexual minorities,” such as queer, nonbinary, gay, lesbian, and gender-variant and trans people; it also provides a way to return to critical questions about social strictures and endemic issues of sexual violence and discrimination faced by women. It provides a chance to return to the meaning of formal equality under the law in India, more than forty years after Indian women’s movements in the 1970s challenged the bounds of constitutional equality.

Beyond India, the judgment has the potential to reach many parts of the postcolonial world, especially the former British Empire, where laws against sodomy were fashioned to resemble India’s Penal Code by the colonial administrations across the empire. Because the criminal codes of former British colonies implemented the same laws against sodomy across the empire, the judgment’s reach might be extended to consider the constitutionality of such laws across South Asia, to Pakistan and Bangladesh, as well as to other former colonies, from Singapore to Malaysia to Uganda.

Justice Nariman’s decision, as well as news reports and commentaries that followed, cite Section 377 as a “Victorian” or “colonial” law that reflected the moral imagination of the colonial government, which enacted the Indian Penal Code in 1861. In the days after the decision, many commentators have proclaimed that the ruling throws off the yoke of colonialism. Yet to declare this moment as the inevitable end of an outdated colonial law and the logical next step for social progress may not be a sufficient critique of the effect of these longstanding laws. There is no question that the law against sodomy reflected conceptions of same-sex and nonreproductive sexual acts in the nineteenth century that came to be broadly understood as “sodomy.” For example, Section 377 reproduced public, legal, and scientific discourses about homosexuality and same-sex desires across Europe and much of the colonial world that linked consensual same-sex behavior with bestiality and sexual violence against children. The code reflects the bias of these associations, and the sections on bestiality and sexual violence against children remain on the books as Section 377.

However, to describe the function of the law as solely derivative of outdated “Victorian morals” would be a false and dangerous claim to progress in a moment of rising authoritarianism and violence against minorities. This violence is perpetrated by right-wing groups who assert that the true anticolonial stance requires a return of Hindu dominance in India; it is a discourse of “liberation” from colonialism that promotes anti-Muslim and anti-lower caste violence. When we state a law is “colonial” without evaluating the history and impact of these laws since the colonial period around the world, we disregard a critical history of how colonialism brought the dramatic reorganization of social and sexual norms among colonized peoples, a history that continues to define social life and law in postcolonial societies today. Colonial-era laws—from civil laws guiding marriage, divorce, and inheritance to criminal laws that policed sexuality—restructured the legal understanding of Indian society and empowered primarily upper-caste Hindu men to reorganize social strictures around upper-caste Hindu conjugal ideals of patriarchal monogamy, heterosexuality, and reproduction. Colonialism was a pivotal moment when upper-caste Hindus, largely men, consolidated power and produced systematic forms of patriarchal power and discrimination in systems of law and institutions of social life. In other words, colonial laws, rather than being a relic of another era, are very much alive; they live through both historic and new ideologies of monogamous marriage, patriarchal domesticity, and heterosexual power that shape social attitudes today. By treating the structure of colonial law as an external structure, a “remnant” of the past, we overlook dangerous ideologies and institutions built around patriarchal, upper-caste Hindu marriage.

Section 377, in its historical role as a tool of harassment and intimidation of sexual minorities, has been the focus of powerful arguments about Indian society and “culture,” promoting a vision where women are restricted to the patriarchal, heterosexual conjugal home and heterosexuality is the sole way to reproduce Indian culture. Indeed, Hindu right-wing groups, secular nationalists, as well as left political movements—all invested in heterosexual marriage—have often insisted that homosexuality is a foreign import, outside the domain of “true” Indian culture. Fighting laws against sodomy is a critical step in undoing such structural norms, but there remain enormous institutional and social biases outside of formal law that shape everyday life. These issues require deep study of the social and sexual strictures produced in late colonialism and postcolonial movements across empires, from the homophobic prescriptions of Christian Evangelicalism in many parts of postcolonial sub-Saharan Africa to right-wing and conservative religious movements in India and elsewhere. Too often, conservative religious majorities have merged the language of anti-imperial nationalism with a violent rhetoric that asserts queer sexualities are “unnatural” and “foreign” imports, brought as the result of colonialism, to be excluded and condemned in society today. The language of anticolonialism is as much a part of exclusionary assertions of a heterosexist nationalism as it is the language of seemingly progressive reform movements.

The language of progress and social evolution characterized the reporting that followed the recent judgment. But constitutional morality holds only for as long as it is availed of as a total rejection of the powerful domain of “social morality" that rules everyday life. Unfortunately, the contemporary moment in India betrays a very different reality: one where, sixty years after the creation of India’s Constitution, minorities and subordinated classes—especially Muslims and Dalits—are systematically targets of public lynchings and mob violence, often as the result of rumors of “deviant” sexualities among minority classes. It is still a place where the rumor of “love jihad” (where Muslim men “steal” or seduce Hindu women) or false rumors of Muslim sexual predation lead directly to public lynchings by mobs of violent people, and often no one is held accountable. Muslims, Dalits, and other minorities right now live in dread of a rumor spread on social media or WhatsApp, or a fake video that portrays sexual liaisons between Hindus and Muslims or lower-caste men and upper-caste women, igniting what are now everyday events of profound sectarian violence. In the face of regular acts of public violence, the function and reach of the new ruling in India is limited at best. And, as scholars like Pratiksha Baxi and Mrinal Satish have argued, the reach of biased “social morality” often extends to the courts and the highly prejudiced decisions and actions by judges themselves, despite reforms in the formal law. The judgment, rather than being heralded as a total success, might be read instead as a mandate that requires much more than language changes to the penal code to see real transformations in people’s access to justice.

What remains after the end of the sodomy law are the myriad laws that continue to be on the books that lead to the harassment of gender non-normative, gender nonbinary, queers, and people engaged in sex work. The claims about constitutional morality mandate a new look at seemingly settled laws, criminal laws that remain on the books and received comparatively little media coverage. The ruling opens up that possibility. Justice Nariman emphasized that there must be “no presumption of constitutionality” for laws originally created before the making of the Indian Constitution, which opens up the entire Indian Penal Code and other parts of criminal law for reevaluation.

Indeed, the Indian Penal Code as a whole may require reevaluation to adhere to “constitutional morality.” As scholars like Anjali Arondekar have shown, Section 377 was rarely prosecuted; it was a law used more often as a tool of intimidation and harassment by the police and as a way for the state to regulate queer bodies. Even so, many other laws are often prosecuted and applied selectively against sexual minorities with dramatic consequences. These laws include sections on solicitation, public nuisance, and public obscenity. Indeed, in the ruling, the question of public decency continued to linger: the judgment explicitly states displays of affection among members of LGBT community are acceptable “so long as it does not amount to indecency.” And perhaps the most difficult criminal laws to contain are those against trafficking. As scholars like Prabha Kotiswaran have argued, antitrafficking laws, although framed around the safety of vulnerable children, have functioned instead as a way for the state to police the lives of women, queer people, and the many adults who choose to make a living through legal acts of sex work.

An important moment in the decision occurred when Justice Nariman asserted that sensitivity training was necessary for the police and media. Yet sensitivity training would require a total reevaluation of laws still on the books that are regularly used to harass sexual minorities and women. These policies will continue to shape the lives of sexual minorities every day in postcolonial India, particularly for lower-class, lower-caste, Muslim, third-gender, and trans communities. Scholars of sexuality like Ani Dutta have demonstrated that communities of impoverished sexual minorities in rural and semi-urban areas are often disproportionately affected by violent forms of policing. In addition, state initiatives under the guise of “public health” and “welfare” continue to empower the police to harass and imprison disadvantaged Devadasi and Dalit communities, as well as working women who live outside of monogamous marriage. People are policed, condemned, or even killed and disappeared from public view through abuses of the law, with little redress for the systematic violence they face at the hands of police, clients, landlords, or sexual partners.

Beyond laws that police sex work, public space, and the lives and bodies of nonnormatively gendered people, the judgment may help us reevaluate the reach of reforms for sexual harassment in both civil and criminal law that require evaluation under terms of formal equality. For example, certain sections in the India Penal Code limit the reach of sexual harassment provisions solely to women, in language that defines criminal harassment as the “outrage of the modesty of a woman.” But who gets to be a modest woman? Why do these laws not address other subordinated classes, particularly sexual minorities? While legal reforms have led to more structures to address sexual harassment of women, trans, queer, and gender nonbinary peoples, these groups often experience disproportional forms of sexual harassment, by the police and in employment.

As a historian of sexuality, I am encouraged by the call to return to history to critically evaluate the violence and exclusion faced by sexual minorities. What does it mean to indict history for its wrongs? It means detailing the structural reparations and protections needed to account for the wrongs committed against a huge number of minorities whose sexual practices are perceived to be outside the norm of upper-caste Hindu conjugality. It means understanding who and what are implicated in history’s apology, especially by naming and holding accountable the protagonists of this exclusionary past who authored this history. It means continuing to write the history of sexual minorities in postcolonial India, the violence they faced and the diversity of sexual practices that continue to be practiced in the face of social exclusion and condemnation. To understand this apology requires detailed historical investigations of the many other laws that police space, comportment, and social life, that have fostered an environment of harassment and policing for sexual minorities and women. It is to debate how we may expand the reach of the Indian Constitution as a flexible document that may help shape shared values of democratic societies in the face of a virulent populism that seeks to deny dignity and equality to many people. Facing these difficult pasts, of history’s wrongs, is essential to imagining a different future.

—Durba Mitra, Faculty Associate (on leave 2018–2019), Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.

Weatherhead Center Faculty Associate Durba Mitra is an assistant professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Harvard University. She is also the Carol K. Pforzheimer Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. Her research interests include the history of sexuality and gender in colonial India and across the colonial and postcolonial world.

Captions

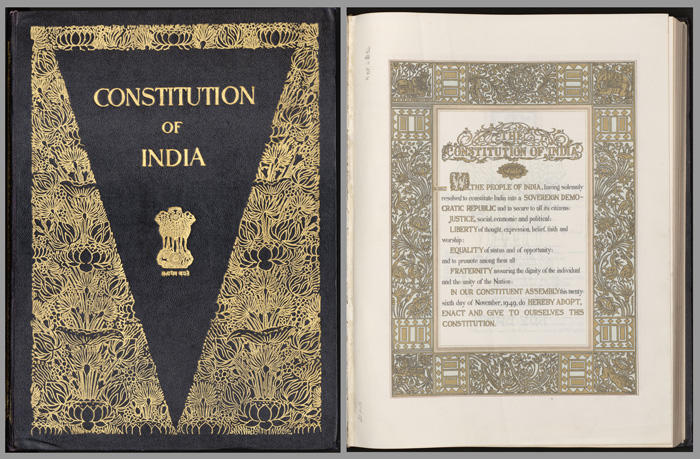

1. Cover (left) and Preamble (right, page 7) of the Constitution of India. Credit: Library of Congress, World Digital Library

2. First slideshow: Image 1, Image 2, Image 3.

3. Second slideshow: Image 1, Image 2, Image 3.